Adventures in Address Space Inference

12 September 2025

Introduction

SYCL is a language that allows standards compliant C++ code to be compiled for accelerator and GPU devices. As part of this compilation, SYCL implementations use a type inference system to derive address space qualifications for pointers. In this post I shall detail the journey Codeplay took to replace their SYCL implementation’s inference engine and give an overview of how the new system works.

Of course, I do not wish to claim that this is all my own work; I was merely the person who happened to work on it the longest. Other Codeplayers who worked on this are as followed:

- Duncan Brawley

- Harald van Dijk

- Peter Žužek

- Victor Lomüller

As well as many other people who I am not able to mention here.

This post was entirely written by a human and contains authentic human mistakes.

Some Background

Codeplay’s ComputeCpp and Intel’s DPC++ compilers both implement the SYCL standard. This standard defines a “single source” model where the same C++ source can be run on both the x86_64/ARM host device as well as any attached GPU or accelerator chips. It also defines a number of helper functions and wrappers to make data and code transfers to the device as easy as possible.

A Mental Model of the Memory Model

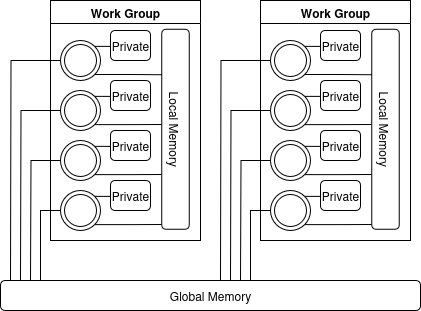

GPUs and other accelerator chips have complex memory configurations. Some memory on the device is only visible to a single work item, whilst other memory is visible to everything but with higher latency. Since early versions of SYCL inherited many things from OpenCL, it makes sense to look at the memory model used there.

OpenCL code is run on a number of “work groups”, which are then divided further down into “work items”. Work items can be thought of as similar to threads in host code that run in lockstep. With this architecture, we can see that there are three different scopes that memory can exist in:

- Private: Available to only a single work item.

- Local: Available and shared between all work items in a single work group.

- Global: Shared between all work items regardless of work group.

Reads and writes to memory need to know what type of memory to access, so languages that compile to OpenCL extend

the type system with so called address spaces to contain this information. Instead of an int *, OpenCL C has

__global int *, __local int * and so on. This follows similar language rules to CV qualifiers like const.

However, having to specify types with a language extensions turned out to be rather clunky and made it hard to share

code between the host and device. To solve this, in OpenCL 2.0 a new address space was added: generic. Pointers of any

address space can be implicitly cast to and from their equivalent generic pointer type, allowing developers to only

use generic pointers in their code and not worry about address spaces. This also enabled a feature called USM

(unified shared memory), where the host could call device allocation functions and get a vanilla C pointer that it can

pass to device code rather than having to fiddle around with OpenCL buffers.

However, like many radical OpenCL 2.0 features, this became an optional feature in OpenCL 3.0. Since it also had reduced performance on some devices, specifying or generating explicit address spaces where possible is preferred over using the generic address space.

Introducing Inference

From the discussion above, it’s easy to see how to get the best of both worlds: let the end user specify their code without explicit address spaces and let the compiler do the heavy lifting and automagically work out the appropriate address spaces.

Among it’s other SYCL features, ComputeCpp included a pass that did just this for device code. It would consume Clang AST, infer the address space required for each pointer, and create new versions of each function with the correct pointer address spaces. I didn’t have a chance to take a deep dive into how this system worked exactly, since it was going to be replaced anyway and had the menacing legacy code aura that threatens to consume all who touch it.

For anyone interested, however, Victor Lomüller has done a talk about it, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKX6EMEib4g .

The main limitation with this system was that it required each pointer had to have precisely one address space which was deduced as part of its initialization. For example:

int* a = some_func(); // the address space of a will be dependant on the return type of some_func

int* b; // default address space is private

b = another_func(); // error if some_func doesn't return a pointer to private

This caused issues for modern SYCL code, which was moving towards USM pointers where the information required to infer a pointer’s address space can appear after its definition. Since Codeplay wanted to preserve support for devices that didn’t support generic pointers, setting the default address space as “generic” wasn’t a viable solution.

With pressure to support USM growing, Codeplay set up a crack team of software engineers to create a new address space inference system. This new system would:

- Run on LLVM IR, rather than the Clang AST due to counter-intuitive behaviour with template instantiation.

- Function as an LLVM pass or passes.

- Replace all pointers in types in the module with ones with an appropriate address space.

- Solve these address spaces wherever they appear, rather than assuming the first access is the correct address space.

- Detect when a pointer can point to multiple address spaces and convert that pointer to the generic address space if possible.

Implementing the System

With our goals in place, we decided to spin up a new project named “Address Space Prototype” or “ASP-Infer” for short. Of course, this name stuck even beyond the prototype stage, and we didn’t have a chance to come up with a cool backronym for it (maybe something snake related?).

Putting together a Prototype

The implementation was originally based on the paper “Complete and Easy Bidirectional Typechecking for Higher-Rank Polymorphism” by Jana Dunfield and Neelakantan R. Krishnaswami. However, we ended up diverging from it fairly quickly, so our implementation and terminology is likely very different from theirs.

To avoid having to provide a primer on LLVM IR in this article, I’ll define a simple language that is close enough to LLVM IR and give examples using that instead. We’ll start with simple constructs, and then build up as we add complexity. To start, let’s define our language as having the following:

- Immutable values.

- Assignment expressions, where the right hand side is one of the following:

- Another value.

- An integer literal which may be implicitly converted to any pointer type.

- A function call to either

eq(equality checking of pointers) orptr_write(write to a pointer).

- C integer types, bools and address space qualified pointers to integers.

- Address spaces may be either concrete (one of

private,localorglobal) orunknown.

- Address spaces may be either concrete (one of

- Implicit casts from integers to pointers.

- Labels,

gotoandgoto if. - Non-value returns.

LLVM aficionados will realise that this is similar to the single assignment form of LLVM IR, especially once you consider that LLVM instructions can generally be treated as function calls.

Here is some nonsensical example code to use as an example:

local int *local_input = 0x1000;

unknown int *unknown_input = 0x3000;

global int *global_input = 0x2000;

unknown int *target_dest = local_input;

unknown int *fancy_buffer = unknown_input;

unknown int *fancy_dest = global_input;

bool check = eq(target_dest, fancy_buffer);

goto fancy_buffer_write if check else normal_buffer_write;

fancy_buffer_write:

void = ptr_write(dest, 100);

return;

normal_buffer_write:

void = ptr_write(fancy_dest, 200);

return;

Our job here is simple: Replace every unknown with one of private, local, global or generic and do it in such

a way that we don’t introduce any type errors. We do this in two stages; the solving stage and the duplication

stage. Both of which are implemented as LLVM IR passes.

To start off with, we first need to go to the analogy store and get a supply of bags for putting address spaces in. We

also gain the ability to create arbitrary or unsolved address spaces, which we will count up as __a, __b, __c

and so on.

With these tools, we can loop through each statement in the module and do the following:

- Look at the left hand side (the “returned” value).

- For each address space that is

unknownin its type, create a new “unsolved” address space and then stamp that unsolved address space onto the appropriateunknownvalue to keep track of the mapping. - Put either the unsolved or concrete address space into a new bag and put that bag somewhere safe.

- Then look at the function or assignment itself, and follow some appropriate rules:

- If it is a value assignment, put the address space of the right hand side into the bag that contains the address space used for the left hand side.

- If it is the function

eq, find the bags containing the address spaces of each of the two arguments. Then pour the contents of one into the other. - Any other functions do nothing special.

Applying this on the previous example, we get the following:

local int *local_input = 0x1000;

__a int *unknown_input = 0x3000;

global int *global_input = 0x2000;

__b int *target_dest = local_input;

__c int *fancy_buffer = unknown_input;

__d int *fancy_dest = global_input;

bool check = eq(target_dest, fancy_buffer);

goto fancy_buffer_write if check else normal_buffer_write;

fancy_buffer_write:

void = ptr_write(dest, 100);

return;

normal_buffer_write:

void = ptr_write(fancy_dest, 200);

return;

The three input values at the start create three bags; {local}, {__a}, {global}. The following three assignments add

new values to these bags: {local, __b}, {__a, __c}, {global, __d}. Then the equality function combines the first two

bags together resulting in {local, __b, __a, __c}, {global, __d}. The modified module and the bags are the result of

the solving stage.

Of course, we can’t emit the unsolved address spaces directly, so we need to identify which concrete address space to use for each address space. This is done by the duplication pass, whose name will make sense later:

- For each unsolved address space in the module, look up which bag it corresponds to and count how many concrete address spaces it contains.

- If there are zero, there are no constraints on the address space so we leave it unsolved.

- If there is exactly one, then we convert it to that address space.

- If there are more than one, then we convert it to either the

genericaddress space (if it is supported) or raise an error.

With our example, __b, __a and __c both share a bag with local, so get replaced with local. __d shares a

bag with global and so gets replaced with global itself. This results in the final value of our module being the

following:

local int *local_input = 0x1000;

local int *unknown_input = 0x3000;

global int *global_input = 0x2000;

local int *target_dest = local_input;

local int *fancy_buffer = unknown_input;

global int *fancy_dest = global_input;

bool check = eq(target_dest, fancy_buffer);

goto fancy_buffer_write if check else normal_buffer_write;

fancy_buffer_write:

void = ptr_write(dest, 100);

return;

normal_buffer_write:

void = ptr_write(fancy_dest, 200);

return;

After that, we go through the module again, and replace any pointers that are still unsolved with private. These are

pointers with no restrictions on their address spaces, so they can be any value. In our example we don’t need to do this

as all pointers were solved.

This whole process is able to fully resolve address spaces in code of any complexity that is written in our simple toy language. This language is very restrictive though, so we need to expand both the language and our inference rules.

Figuring out Functions

In our rules for eq we define the function as having two input bags that are combined into one single bag. Let’s steal

some syntax from C++ to represent this, and define a few more functions:

bool eq<A>(A int *, A int *);

B int *memcpy<A, B>(A int *, B int *, int);

A int *get_ptr_offset<A>(A int *, int);

For each templated address space (A, B, etc.) we can replace it with any arbitrary address space, whether it be

concrete or unsolved. With these definitions for all functions, we can replace the hardcoded logic for eq in rule 2

from the previous section with the following:

- Then look at the function or assignment itself, and follow some appropriate rules:

- If it is a value assignment, put the address space of the right hand side into the bag that contains the address space used for the left hand side.

- If the right hand side is a function, look up the declaration of the function. 1. For each parameter in the declaration that has a concrete address space, add that address space to the bag of the appropriate value passed in. 2. If the return value for the function declaration has a concrete address space, add that to the bag for the assignment’s left hand side. 3. For each templated address space, combine the bags for the respective argument values and/or the expression’s left hand side.

As an example, consider:

A int *do_something_strange<A>(A int *, private int *);

global int *first = 0x1000;

unknown int *second = 0x2000;

unknown int *ret = do_something_strange(first, second);

When we hit do_something_strange, we have two bags:

{global}linked tofirst.{__a}linked tosecond.

We then create a third bag, {__b} for the return value of this function. Taking a look at the function signature, we

know that the second argument has the private address space, so we add it to second’s bag, resulting in

{__b, private}. We also notice that A is used both as the first argument and return value, so we combine the

{global} and {__b} bags together.

Then the result of applying these solutions are as follows:

global int *do_something_strange<global>(global int *, private int *);

global int *first = 0x1000;

private int *second = 0x2000;

global int *ret = do_something_strange<global>(first, second);

There’s some additional work to do with mangling the function name for the new types, but other than that this will be able to solve any function call where a proper declaration can be generated. Since LLVM IR instructions also involve input parameters and return values, this logic can apply to most IR instructions by pretending they are functions.

Discussing Duplication

We now have a system where we are given a templated function declaration and can use it to solve the address spaces of surrounding code. But what about user specified functions? We can’t assume the user will provide these templates for all of their functions, and we want to allow the same function to have multiple solutions.

We will expand our toy language to include the following:

- Functions can be defined with any number of arguments and a return type.

- A

returnexpression that returns a given value from the function.

Then, we will work on another example program:

int *my_func(unknown int *a, unknown int *b, global int *iftrue, unknown int *iffalse) {

bool check = eq(a, b);

goto truebranch if check else falsebranch;

truebranch:

return iftrue;

falsebranch:

return iffalse;

}

Generating a templated declaration is relatively simple: We give the return value and arguments bags like any other

value and solve them in the same way. For my_func, this would result in this:

global int *my_func(__a int *a, __a int *b, global int *iftrue, global int *iffalse) {

// Constrains a and b to the same address space

bool check = eq(a, b);

goto truebranch if check else falsebranch;

truebranch:

// Constrains the return branch to the same address space as iftrue

return iftrue;

falsebranch:

// Constrains the return branch to the same address space as iffalse

return iffalse;

}

Looking at this function, we see that we can substitute __a with any address space we like and still have a valid

function. For stylistic reasons, we use upper case unsolved names, resulting in my_func having a declaration of:

global int *my_func<A>(A int *, A int *, global int *, global int *);

By doing this, we can generate these declarations whenever we see a user specified function. These functions follow the same rules as the built-in functions from the previous section and can be solved in the same way. Two major limitations of this approach are that it does not support recursive or variadic functions, but neither of those are supported in SYCL anyway.

However, even though we have this definition, the function itself is still unsolved and uses the old unknown address spaces. To continue the C++ analogy, we need to do template substitution with the function, making a new “solved” function with the template arguments replaced. To do this we extend the duplication pass earlier to duplicate functions (I told you the name would make sense later):

- For each unsolved address space in the expression, look up which bag it corresponds to and count how many concrete address spaces it contains.

- If there are zero, there are no constraints on the address space so we leave it unsolved.

- If there is exactly one, then we convert it to that address space.

- If there are more than one, then we convert it to either the

genericaddress space (if it is supported) or raise an error. - If the expression is a user defined function, do the following:

- Create an exact copy of that function, and also all of the bags contained within it.

- Update the current expression to be a call to the newly cloned function.

- For each templated unsolved address space, look up the address space to instantiate it with from the call.

- Put that address space in the appropriate bag in the cloned function.

- Call this duplication pass on the newly cloned function.

With that, we are now able to fully handle arbitrary user provided functions. For example, we can go from this:

int *my_func(unknown int *a, unknown int *b, global int *iftrue, unknown int *iffalse) {

bool check = eq(a, b);

goto truebranch if check else falsebranch;

truebranch:

return iftrue;

falsebranch:

return iffalse;

}

void main() {

unknown int *iftrue = 0x8000;

unknown int *iffalse = 0x8008;

private int *first_a = 0x1000;

unknown int *first_b = 0x2000;

my_func(first_a, first_b, iftrue, iffalse);

local int *second_a = 0x1000;

unknown int *second_b = 0x2000;

my_func(second_a, second_b, iftrue, iffalse);

}

To this:

global int *my_func__private(private int *a, private int *b, global int *iftrue, global int *iffalse) {

bool check = eq(a, b);

goto truebranch if check else falsebranch;

truebranch:

return iftrue;

falsebranch:

return iffalse;

}

global int *my_func__local(local int *a, local int *b, global int *iftrue, global int *iffalse) {

bool check = eq(a, b);

goto truebranch if check else falsebranch;

truebranch:

return iftrue;

falsebranch:

return iffalse;

}

void main() {

global int *iftrue = 0x8000;

global int *iffalse = 0x8008;

private int *first_a = 0x1000;

private int *first_b = 0x2000;

my_func__private(first_a, first_b, iftrue, iffalse);

local int *second_a = 0x1000;

local int *second_b = 0x2000;

my_func__local(second_a, second_b, iftrue, iffalse);

}

Time for Types

Until now we’ve only been looking at types that only have a single address. Real world code tends to be more complex, with multiple levels of pointers, structs and arrays. Take this example, with unsolved address spaces:

struct Element {

__a int * __b *Active;

__c int *Stuff[5];

}

struct Container {

__d Element *Elem;

__e Container *Next;

}

Looking at the Container struct, we can generate a list of address spaces by walking through the type tree:

| Container =========================== |

| Elem ========================= | Next |

| *Elem ================== | | |

| Elem.Active | Elem.Stuff | | |

{ __b, __a, __c, __d, __e };

This algorithm can also be reversed, allowing variants of the Container type to be rebuilt from a modified list.

However, one big limitation with this algorithm is that it cannot handle “recursive types” like Container::Next and

will treat the “inner” type as having the same assignments as the “outer” type. For our address space inference system,

this unfortunately means that all elements of a linked list or tree must share the same address space solutions.

With the ability to produce and consume these lists, it is relatively easy to update the address space solver and duplicator system to run on each list element-wise rather than only on a single address space. In theory, anyway. As you can imagine, retrofitting this onto our existing code required quite a bit of troubleshooting and edge case handling.

With the expanded type support, we needed to handle some special operations relating to manipulating pointers. But those were relatively simple:

- Dereferencing a pointer is popping the last element from the input’s type list, and solving that against the output.

- Address-of-ing a value is pushing a new address space onto the input’s type list and using that as the output.

- Offsetting into a pointer is parsing the input type and figuring out the appropriate member element to use as the output.

Handing out Homework

There were a lot of other problems we needed to solve, however for the sake of brevity I’ll do the time honoured tradition of handwaving them away and saying “they are left as an exercise for the reader”:

- How do you handle global variables?

- How do you handle “PHI Nodes”, which are what LLVM uses to represent loops?

- How do you handle casting two completely unrelated types being cast to each other?

- What if the user provides a function declaration with no body?

- Can we actually support variadic functions or recursion in some way?

- How do you handle C++ exceptions and

goto?

Some of these we were able to solve, others we decided were likely impossible. Enjoy.

The End of the Project

With the prototype version in place, we then started looking into upstreaming it to either LLVM or the DPC++ SYCL implementation. Unfortunately, a number of issues arose as we started looking into doing so.

Removing Inference Mode

As a reminder, our inference system has two modes:

- Inference mode, where we allow a subset of SYCL where any unsolvable address spaces (either due to conflicts or having unhandleable code structures) is a hard error.

- Generic mode, where those same unsolvable address spaces are lowered to generic pointers.

OpenCL is somewhat of a relic in the modern world of CUDA and ROCm, both of which have native support for generic pointers. Since generic pointers are commonplace, it is also supported in most modern OpenCL implementations as well. This means that the desire for supporting devices without generic pointers has gone down over time, especially in SYCL, which advertises itself as cross-vendor.

In addition, the rules for inference mode are not specified by the SYCL spec and inconsistent between the original inference system and the new one. The new inference passes run on LLVM IR, and the mapping between it and C++ are non-trivial and hard to add to a specification document.

Because of these two factors, the decision was made to remove the “inference” mode entirely and only support generic mode. Inference passes will remove generic address spaces on a “best-effort” basis and leave existing generic address spaces in the module.

Opaque Pointers

In the section discussing type inference earlier I talked about how we could use the type information in LLVM to work with pointers and solve individual struct members. This was possible because LLVM stores full type information with pointers as well as use explicit casts between different types.

Of course, while we were working on this, upstream LLVM decided to remove all that information and treat all pointers

in IR as simply void *. They did this to make LLVM IR less verbose and more expressive, but it turned out we really

needed that inflexible verbosity.

To solve this, we ended up rolling out a very simple type inference system on top of the address space inference. This wasn’t able to fully recreate the types of yore, but since we were no longer aiming for complete type removal, it was good enough to solve most address spaces.

Upstream Inference

While we were working on our type inference system, LLVM rolled out their own version of it. It was initially only available for Nvidia targets, but seemed trivial enough to extend to AMD as well. It was also enabled by default in the DPC++ SYCL compiler implementation, so was known to function with SYCL code.

It was a simpler and more naive pass than ours and didn’t include our fancy duplication logic, so by pure numbers on synthetic examples ours performed better. However, there wasn’t that much of a performance difference in real world code.

Inside functions themselves, LLVM’s inference pass was able to replace most address spaces and those that did remain were not on hot enough paths to really matter. Our duplication system would have helped, except that most code compiled for devices tends to be aggressively inlined to the point where most kernels are just a single giant function anyway.

Conclusion

With the above issues there was an increasingly growing “why are we doing this?” elephant in the room. Eventually, it grew to the point where we decided to cut the project entirely and stop working on it. Which is a shame, as the project resulted in an interesting and elegant solution.

Hopefully though, the design can live on in the form of this blog post. Perhaps it will remain only a small curiosity for people to skim through while drinking their coffee. Perhaps it will end up adapted to solve some other problem somewhere. There’s really no way to infer the future, after all.