Improving Triton FlashAttention Performance on Intel GPU

02 September 2025

GPU tensor core and data feeding

Tensor Cores are specialized processing units within a GPU. Introduced in 2017 by Nvidia in their Volta GPU architecture, this specialized hardware is used to accelerate matrix operations, such as those used in AI, deep learning, and high-performance computing tasks.

Tensor Cores have also improved computation throughput without degrading accuracy (or only slightly) by combining lower-precision data types for operands with higher-precision accumulation, which is known as mixed-precision. Mixed-precision computation has unlocked AI computation performance, as AI models are able to provide results similar to higher-precision calculations while reducing memory usage. But this last point is out of the scope for this blog post.

In short, Tensor Cores have completely revolutionised the calculation of AI models by enabling high-performance, high-throughput matrix multiplication: each generation of GPUs increased the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs) the hardware is able to compute per second by order of magnitude, as shown in the table below.

| GPU | GP100 (Pascal) | V100 (Volta) | A100 (Ampere) | H100 (Hopper) | HGX B200 (Blackwell) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensor Cores | N/A | 640 | 432 | 528 | TBD |

| Float 16 bits | 21.2 TFLOPs | 130 TFLOPs | 312 TFLOPs | 989.4 TFLOPs | 2,200 TFLOPs |

| Float 32 bits | 10.6 TFLOPs | 16.4 TFLOPs | 156 TFLOPs (19.5 TFLOPs standard) |

494.7 TFLOPs | 1,100 TFLOPs |

| Float 64 bits | 5.30 TFLOPs | 8.2 TFLOPs | 19.5 TFLOPs (9.7 TFLOPs standard) |

66.9 TFLOPs | 37 TFLOPs |

sources: GP100, V100, A100, H100 and B200

But, now that the hardware is capable of computing a large amount of data per second, the question is: “How can we feed these engines with enough data to really take advantage of their computing capability?” Indeed, if we are not able to continuously supply a large amount of data to these Tensor Cores, as powerful the compute unit may be, it will have to wait for data to be brought to the computing engine (from memory), and computing performance will be limited by this.

Another question is how a programmer who is not a hardware expert can take advantage of these very advanced hardware features. One possible answer to this question might be to use Triton. Triton is “a Python-based programming environment for productively writing custom DNN compute kernels capable of running at maximum throughput on modern GPU hardware”, as described on the Triton website. Thus, Triton is an embedded domain-specific language (eDSL) within Python, which allows non-expert users to code an AI kernel and rely on a dedicated Triton MLIR-based compiler to optimise that kernel for a specific GPU target. In this blog post, we will show how hardware limitations and capabilities can be accommodated by the Triton environment, and in particular how register reuse can improve performance.

More computing capacity = More data to feed in

Let’s first step back from the concrete implementation of a kernel and look at GPU architectures.

If we consider simple matrix multiplication : $C += A \times B$, we need to provide Tensor Cores with two input operands A and B and store the output C.

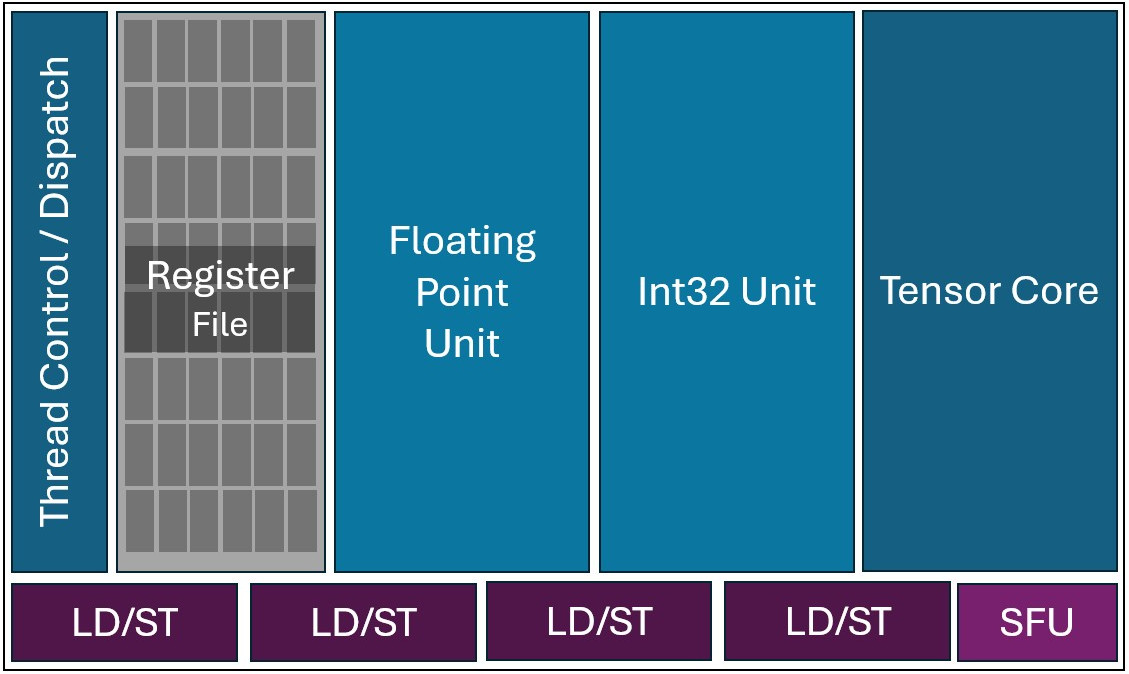

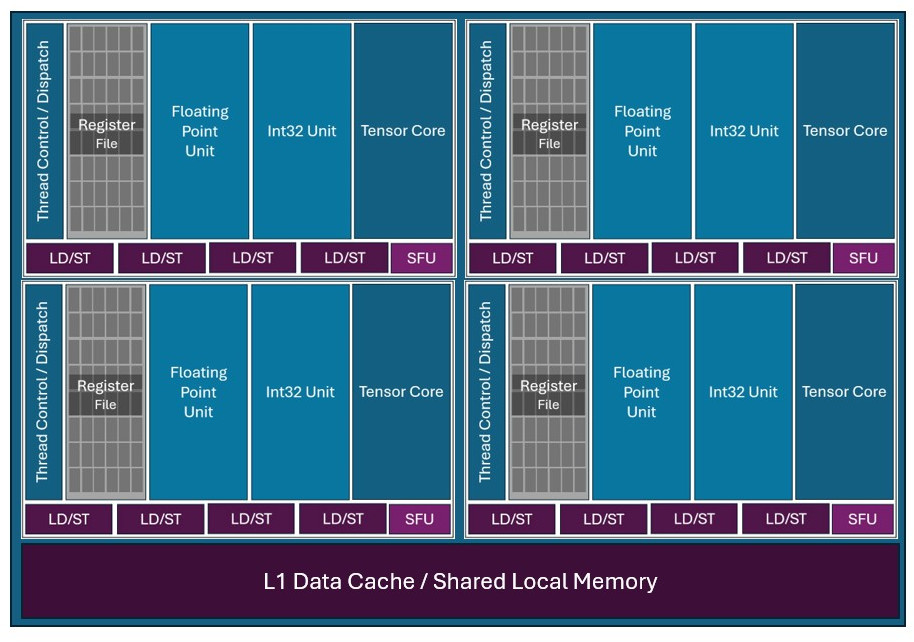

In classical GPU architecture, the operands and outputs are provided to Tensor Cores (also called Matrix Engines or XMX in Intel GPUs) using registers. Registers are a kind of small and fast memory bank (called Register File) located just beside the compute engine, as this can be seen on the following diagrams showing selected parts of an Intel GPU architecture.

Illustration of an Intel Xe2 GPU Vector engine architecture (simplified)

Illustration of an Intel XeCore architecture (simplified)

Basically, the tensor core reads operands A and B from a the Register File and then writes the accumulated output C back to the Register File.

However, as we have seen in Introduction, Tensor Cores have improved significantly, making it possible to compute more and more data per second. But, this implies that we need to feed Tensor Cores with an increasing amount of data to take advantage of their computing power. This raises two issues:

- Data need to be transferred from the Global Memory to the register file

- The capacity of the register file must be sufficient to store all the necessary data.

To address the first point, recent GPUs incorporate dedicated engines to load/store data asynchronously from/to Global Memory. Therefore, these Direct Memory Access (DMA) engines (called Tensor Memory Accelerator TMA in Nvidia architectures) enable to hide the latency of accessing distant memory. As for increasing throughput, the common idea is to achieve that by sharing as much data as possible between Streaming Processors (SM). Indeed, recent Nvidia architectures (Hopper and later) comes with a Thread Block Cluster feature that allows experienced users to reduce the amount of data fetched from distant memory. In this post, we won’t go into more detail about these features and how to take advantage of them, but we can recommend Colfax’s posts on TMA and Thread Block Cluster.

How to deal with the limited size of Register files?

As mentioned above, register files have a limited size and must contain all the live variables we need to execute the user kernel. So, if the user kernel requires more live variables than the number of available registers, the compiler has to resort to register spilling. This technique consists in freeing Register by pushing its contents into memory and then loading it back before the contents can be used. As can one imagine, this extra data movements back and forth to memory can severely impact computational performance. Although compilers do their best to avoid register to be spilled by optimizing the generated code to reuse available registers as much as possible, sometimes, if the amount of live variables are too large, the compiler cannot do its magic and registers have to be spilled.

However, some improvements and techniques can be considered before relying on low-level compilers for “last mile” optimisations.

To this end, the 4th and subsequent generations of Nvidia Tensor Cores can load data (i.e., A and B operands) directly from the Shared Local Memory (SMEM). Instead of putting the whole operands into registers, only a 64-bit matrix descriptor is put into a register. This matrix descriptor specifies the properties of the matrix in SMEM. Based on this information, the Tensor Core is able to directly fetch the operands from SMEM, freeing registers for other variables. The 5th generation of Nvidia Tensor Cores has taken this concept a step further by adding a Tensor Memory (TMEM) dedicated to Tensor Core operands and outputs. So, with this new dedicated on-chip memory, Tensor Cores can perform matrix multiplication without storing any of its operands and output in registers.

Again, I recommend reading Colfax blog post to learn how to use TMEM in your code.

Load and Store Semantics

In the triton language, tl.load and tl.store operations are defined as follow:

tl.load:

Return a tensor of data whose values are loaded from memory at location defined by pointer …

source: https://triton-lang.org/main/python-api/generated/triton.language.load.html#triton.language.load

tl.store:

Store a tensor of data into memory locations defined by pointer.

source: https://triton-lang.org/main/python-api/generated/triton.language.store.html

Thus, the language does not clearly define where the tensor of data is loaded and from where the stored come from. The compiler is therefore responsible for loading the data in the appropriate local memory according to the target GPUs. By default, the operands of an operation must be available in Registers for the operation to take place. So, the default policy for the load operation would be to handle the memory movement from Global Memory to Registers and conversely for the store operation.

However, loading data from Global Memory to Registers takes time (high latency) and loading data ahead of time is not a

suitable solution given the limited number of available registers.

But fortunately, we have an intermediate level in the memory hierarchy: the “L1 Data Cache / Shared Local Memory”.

So, in practice, the compiler will decompose the tl.load into a two-step process:

- From Global Memory to L1 Cache (or SMEM)

- From L1 Cache (or SMEM) to Registers

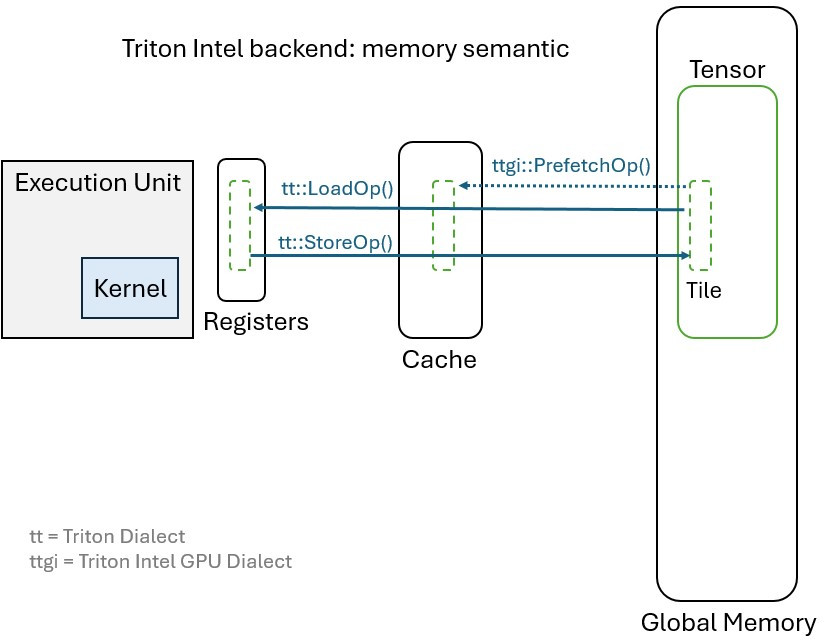

In Intel architectures (Ponte Vecchio GPU Max (PVC) and Battlemage Arc B580 GPU), a hardware-managed cache, i.e., the “

L1 Data cache”, is used to to bring data closer to the compute unit then data evictions are managed by the hardware in

case of conflicts, quite similarly to what is done for CPUs.

The first step of our loading process is therefore achieved by a TritonIntelGPU::PrefetchOp which prefetches the data

from Global Memory to the L1 Cache, then the second step is carried out by the Triton::LoadOp which loads data into

Registers, hopefully from the L1 cache if the data is still available in cache (cache hit).

The diagram below illustrates this process:

Intel Backend Memory Semantic (synchronous)

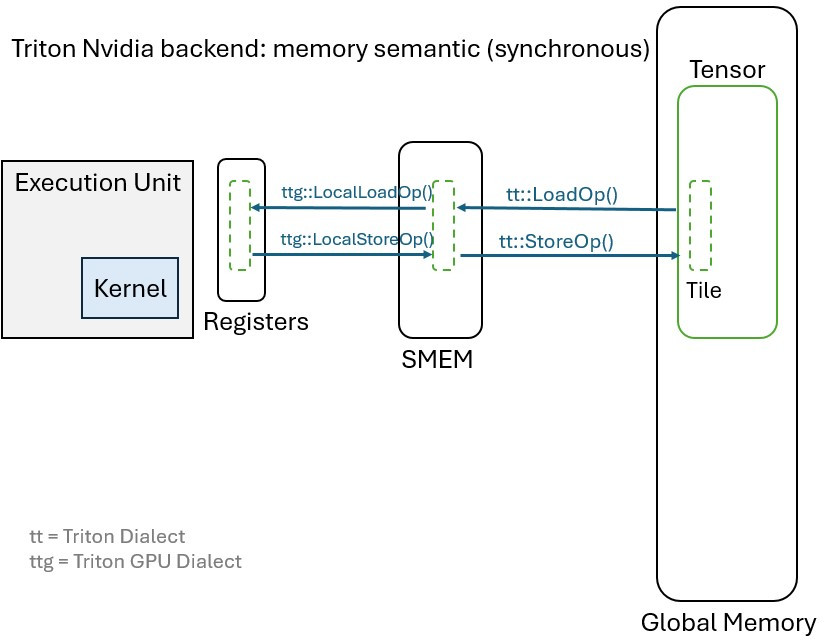

Nvidia has chosen to leverage the Shared Local Memory (SMEM) instead of the cache. SMEM is indeed a scratch pad memory

explicitly managed by the software. Hence, to accommodate the Nvidia backend, we find in the Triton GPU dialect some

operations to manage the SMEM, such as TritonGPU::LocalAllocOp TritonGPU::LocalDeallocOp to allocate and deallocate

a memory buffer in SMEM, but also TritonGPU::LocalLoadOp and TritonGPU::LocalStoreOp to handle the data transfers

between SMEM and Registers.

Consequently, the Triton process for loading and storing data (synchronously) in the Nvidia architecture is as follows:

Nvidia Backend Memory Semantic (synchronous)

NOTE

It’s worth noting here that Nvidia Tensor Core version 4 and later are special operations that do not require their operand to be in Registers, but operands can (or have to be) in SMEM for the mma operation to take place. Consequently, the compiler does not need to explicitly load the tensor from SMEM to register, but the mma operation manages its operands itself.

Variable liveness and Register reservation

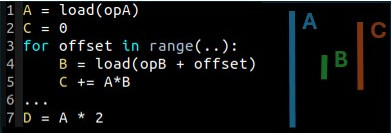

We say that a variable is live at a given point of a program if the variable contains a value that may be used in the future. In the following example, the variable A is live from line 1 to line 7, where the last use of the variable A is found. As for the variable B, its liveness only spans from line 4 to line 5. When register assignment is performed during compilation, the compiler attempts to keep A in registers for all its lifespan. So, in our example, if A needs $NumReg_A$ registers to be stored, this means that $NumReg_A$ registers will be reserved for A across the loop, and thus the compiler needs to fit the variables used between line 1 and 7 in $N - NumReg_A$ registers, with $N$ being the total number of registers available.

Variable liveness simple example

It is therefore easy to understand that in such a kernel, if the variable A is large and the kernel processing between lines 2 and 7 is also consuming register, the compiler may have a hard time to allocate registers while avoiding register spills.

This is exactly what happens in the widespread case of FlashAttention version 2.

The FlashAttention v2 Forward pass algorithm in pseudo-code is:

1 # Inputs : Q, K and V are 2D Matrices in Global Memory

2 def FlashAttention2_forward(Q, K, V):

3 O = torch.zeros_like(Q, requires_grad=True)

4 L = torch.zeros(Q.shape[:-1])[...,None]

5

6 Q_BLOCKS = torch.split(Q, BLOCK_SHAPE)

7 K_BLOCKS = torch.split(K, BLOCK_SHAPE)

8 V_BLOCKS = torch.split(V, BLOCK_SHAPE)

9

10 Tr = len(Q_BLOCKS)

11 Tc = len(K_BLOCKS)

12

13 for i in range(Tr):

14 Qi = load(Q_BLOCKS[i]) # Load data from Global Memory to SRAM

15 Oi = torch.zeros(BLOCK_SHAPE) # No load required, Initialized on chip

16 li = torch.zeros(BLOCK_SHAPE) # No load required, Initialized on chip

17 mi = NEG_INF # No load required, Initialized on chip

18

19 for j in range(Tc):

20 Kj = load(K_BLOCKS[j]) # Load data from Global Memory to SRAM

21 Vj = load(V_BLOCKS[j]) # Load data from Global Memory to SRAM

22

23 KTj = Kj.transpose()

24 S_ij = matmul(Qi, KTj)

25

26 P_ij, m_block_ij, mi_new, li_new = online_softmax(S_ij, mi, li)

27

28 P_ij_Vj = matmul(P_ij, Vj)

29 Oij = (li/li_new) * torch.exp(mi - mi_new) * Oi + (torch.exp(m_block_ij - mi_new) / li_new) * P_ij_Vj

30

31 # update li and mi

32 li = li_new

33 mi = mi_new

34

35 Oi = Oij / diag(li)

36 O.store(Oi, i) # Store data to Global Memory as the i-th block of O

37 L.store(li, i) # Store data to Global Memory as the i-th block of L

38

39 return O, L

In the second version of the implementation of the FlashAttention model, the loop order has been reversed to promote data locality. As long as there is enough local memory (or registers) to contain all the needed data, this algorithm works fine and provides significant performance improvements compared to FlashAttention v1 (in the paper, the authors mention 2x faster for the Cutlass implementation and 1.3-1.5× faster in Triton on an Nvidia Ampere GPU A100). Deployed on a GPU target, line 13-37 constitutes the computing kernel that is dispatched to a Thread Block/Work-Group ( i.e. a SM/XeCore). As you can see, variable Q is loaded before the loop (line 14) and remains live across the loop.

The long lifespan of variable Q is even more problematic in the causal variation of the FlashAttention implementation. The causal variation is defined in the paper as :

One common use case of attention is in auto-regressive language modeling, where we need to apply a causal mask to the attention matrix S (i.e., any entry S𝑖 𝑗 with 𝑗 > 𝑖 is set to −∞).

The Triton implementation of FlashAttention v2 with causal mask is as follow:

@triton.jit

def _attn_fwd(Q_block_ptr, K_block_ptr, V_block_ptr, sm_scale, M, N_CTX: tl.constexpr, #

BLOCK_M: tl.constexpr, BLOCK_DMODEL: tl.constexpr, #

BLOCK_N: tl.constexpr):

start_m = tl.program_id(2)

...

# initialize offsets

offs_m = start_m * BLOCK_M + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_M)

offs_n = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_N)

# initialize pointer to m and l

m_i = tl.zeros([BLOCK_M], dtype=tl.float32) - float('inf')

l_i = tl.zeros([BLOCK_M], dtype=tl.float32) + 1.0

acc = tl.zeros([BLOCK_M, BLOCK_DMODEL], dtype=tl.float32)

# load scales

qk_scale = sm_scale

qk_scale *= 1.44269504 # 1/log(2)

# load q: it will stay in SRAM throughout

# The liveness of the variable `q` begins at this point (q is live)

q = tl.load(Q_block_ptr)

# stage 1: off-band

# range of values handled by this stage

lo, hi = 0, start_m * BLOCK_M

K_block_ptr = tl.advance(K_block_ptr, (0, lo))

V_block_ptr = tl.advance(V_block_ptr, (lo, 0))

# loop over k, v and update accumulator

for start_n in range(lo, hi, BLOCK_N):

start_n = tl.multiple_of(start_n, BLOCK_N)

# -- compute qk ----

k = tl.load(K_block_ptr)

qk = tl.zeros([BLOCK_M, BLOCK_N], dtype=tl.float32)

qk += tl.dot(q, k)

m_ij = tl.maximum(m_i, tl.max(qk, 1) * qk_scale)

qk = qk * qk_scale - m_ij[:, None]

p = tl.math.exp2(qk)

l_ij = tl.sum(p, 1)

# -- update m_i and l_i

alpha = tl.math.exp2(m_i - m_ij)

l_i = l_i * alpha + l_ij

# -- update output accumulator --

acc = acc * alpha[:, None]

# update acc

v = tl.load(V_block_ptr)

acc += tl.dot(p.to(tl.float16), v)

# update m_i and l_i

m_i = m_ij

V_block_ptr = tl.advance(V_block_ptr, (BLOCK_N, 0))

K_block_ptr = tl.advance(K_block_ptr, (0, BLOCK_N))

# stage 2: on-band

# loop over k, v and update accumulator

for start_n in range(lo, hi, BLOCK_N):

start_n = tl.multiple_of(start_n, BLOCK_N)

# -- compute qk ----

k = tl.load(K_block_ptr)

qk = tl.zeros([BLOCK_M, BLOCK_N], dtype=tl.float32)

# This is the last time the variable `q` is used.

# Unless the compiler being able to remove the loop,

# the liveness of the variable `q` will ends at the end of the loop.

qk += tl.dot(q, k)

# -- apply causal mask ----

mask = offs_m[:, None] >= (start_n + offs_n[None, :])

qk = qk * qk_scale + tl.where(mask, 0, -1.0e6)

m_ij = tl.maximum(m_i, tl.max(qk, 1))

qk -= m_ij[:, None]

p = tl.math.exp2(qk)

l_ij = tl.sum(p, 1)

# -- update m_i and l_i

alpha = tl.math.exp2(m_i - m_ij)

l_i = l_i * alpha + l_ij

# -- update output accumulator --

acc = acc * alpha[:, None]

# update acc

v = tl.load(V_block_ptr)

acc += tl.dot(p.to(tl.float16), v)

# update m_i and l_i

m_i = m_ij

V_block_ptr = tl.advance(V_block_ptr, (BLOCK_N, 0))

K_block_ptr = tl.advance(K_block_ptr, (0, BLOCK_N))

# epilogue

m_i += tl.math.log2(l_i)

acc = acc / l_i[:, None]

# The variable q liveness ends at this point

tl.store(Out, acc.to(Out.type.element_ty), boundary_check=(0, 1))

This code is simplified version of the triton implementation of FlashAttention under MIT license.

As you can see we now have two loops (one for calculating the data to which the mask does not need to be applied, and

another for calculating the data to which the mask does need to be applied).

Our point is that variable q that loads a chunk of the Q matrix is live for the instruction tl.load(Q) until the

second loop where variable q is read for the last time.

When the target GPU architecture is able to load its operands directly from SMEM or TMEM (as discussed in the previous

section), this is less of a problem because these memories are larger than the register files.

But when the target GPU does not have this capability, such as Intel Ponte Veccio and Battlemage GPUs, the variable has

to reside in registers.

Thus, registers should be dedicated to saving this variable all along the kernel execution.

Consequently, if variable q is large, many registers will be reserved for saving this variable and the register

allocator will be forced to spill registers.

Reduce Variable liveness: a way of helping the register allocator

The register allocator’s difficulty in assigning registers without spilling comes from the fact that some variables are live for a long period of time, which reduces the number of registers available for other variables. Even worse, the high pressure on registers can prevent the compiler from applying other optimisations such as loop unrolling (which requires additional registers).

As a consequence, to reduce the liveness of variables, when possible, relaxes the constraints on register allocations and helps the compiler avoid register spills and further optimise the code.

An optimization pass to reduce variable liveness

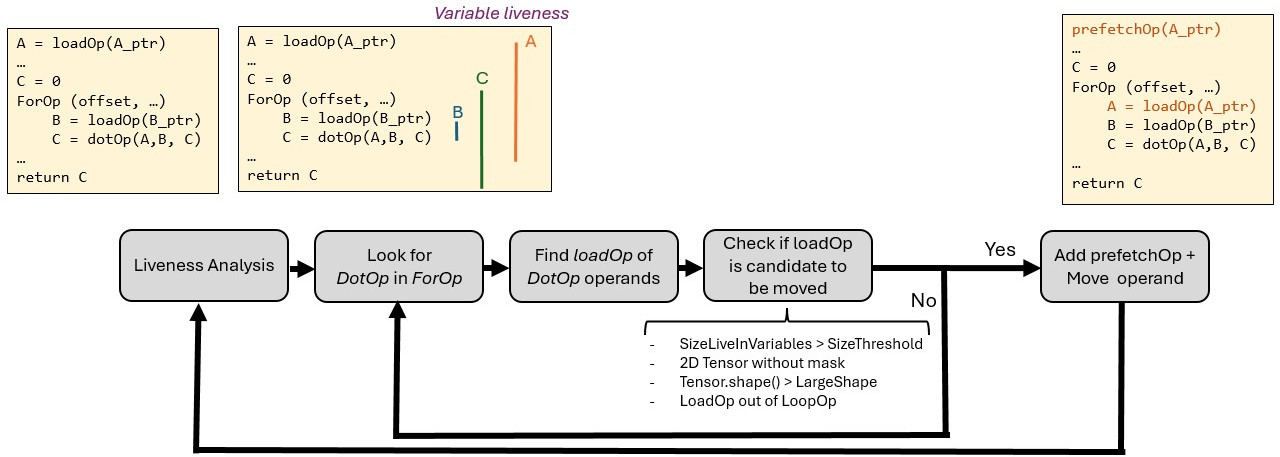

In the XPU backend of the Triton compiler, we have added an optimization pass which aims to reduce variable liveness where possible. To this end, the pass attempts to bring load operations closer to the actual uses of the loaded data.

Reduce Variable Liveness pass diagram

The diagram above shows how the compiler pass works to reduce the liveness of DotOp operands.

The first step consists in running the MLIR

upstream liveness-analysis pass.

This analysis computes the liveness of each variable in the source code. This will allow us to check the size of live

variables at a specific point in the source code.

In the second step, the pass looks for DotOp (i.e., the matrix multiplication operation) in a For loop. Currently,

the pass only considers DotOp in For loops as anchor because it is a resource-consuming operation that is critical

to the performance of AI kernels.

But the pass can be extended to other cases in the future.

The third step is to retrieve the loadOp that loads the DotOp operands.

In brief, the pass rolls back the def-chain of the DotOp operands and returns the loadOp when it is found.

Next, the pass checks if the loadOp is eligible to be moved. To be a candidate, a few conditions must be met:

- The total size of the live-in variables must be greater than a defined threshold. This condition aims to assess the occupancy level of the register file.

- The data loaded must be a 2D Tensor (with no loading mask).

- Empirically, we observe that loading a large amount of data is not the only criteria to determine if moving

the

loadOpis needed. The Triton language defines kernel at block/work-group level, but this group is then handled by multiple warps/sub-group (and threads/work-items). This sub-division into warps has an impact on the way data is loaded and on the register assignment policy. As a result, the amount of loaded data must be large, but, also, the shape of the data on the dimension that is not split between warps must be large enough for the proposed optimisation to be relevant. - The

loadOpmust be outside the loop body, i.e., the operand must be a live-in variable of the loop.

If the conditions are not met for any of the operands, the pass tries to optimise the next DotOp if any.

Otherwise, if these conditions are met for at least one of the operands, the pass proceeds to the last step, which takes

care of moving the loadOp.

If the loadOp has only one user (i.e., the DotOp), the load operation is sinked into the loop and a prefetch

operation (prefetchOp) is inserted where the loadOp was initially located, as shown on the diagram.

The prefetch operation fetches the data from global memory into the cache. As a result, when the actual load takes

place, the data is loaded from the cache and not from the global memory.

The case where the loadOp has more than one user, is a little more complex as the loadOp cannot simply be sunk into

the loop, but the pass must ensure that a load operation takes place before accessing the data.

As loading data from the cache is not expensive, we chose to add another loadOp for subsequent uses. Hence, the

liveness of the tensor is still reduced and the low-level compiler (igc for intel target) is able to perform its

optimisations with less constraints on registers.

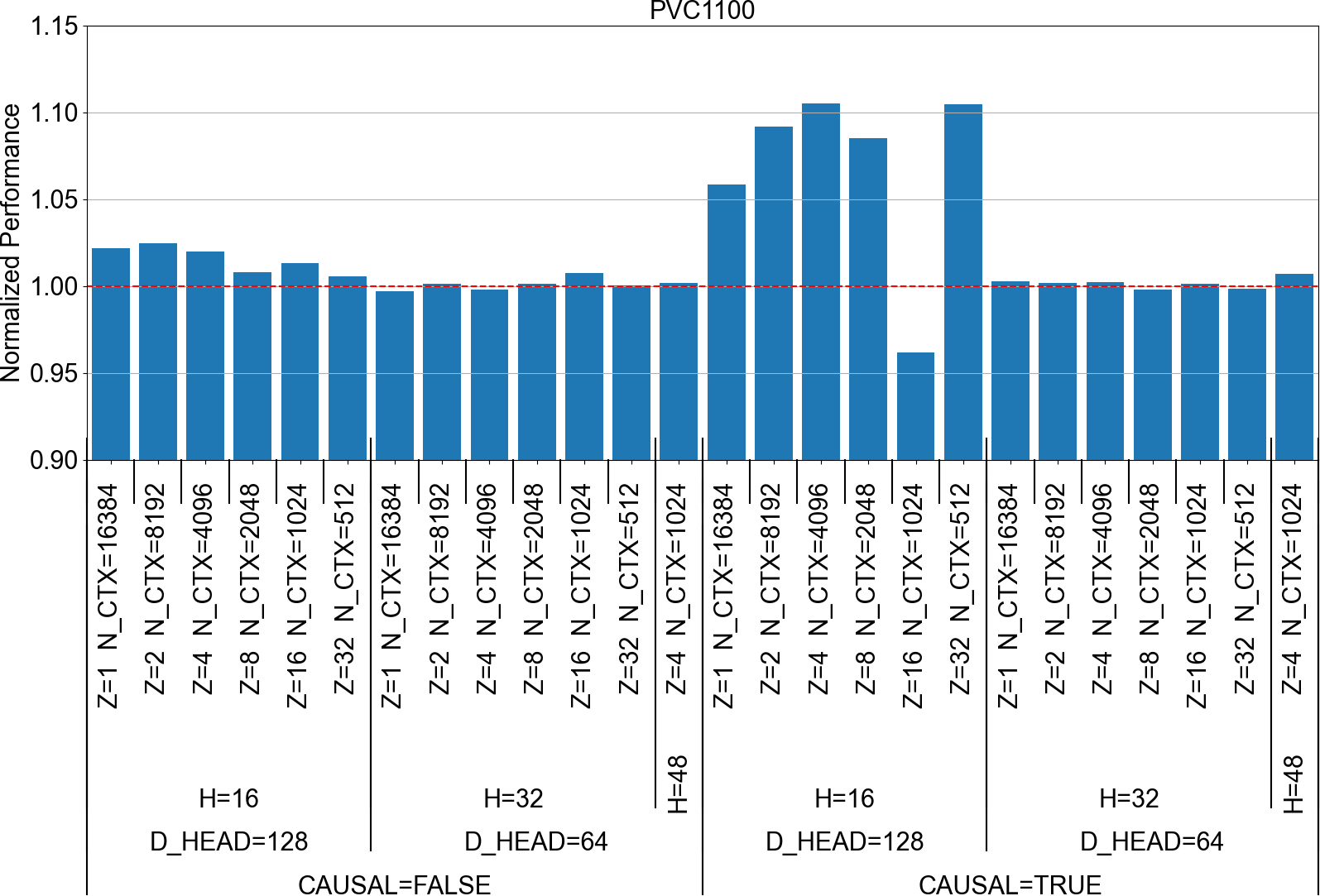

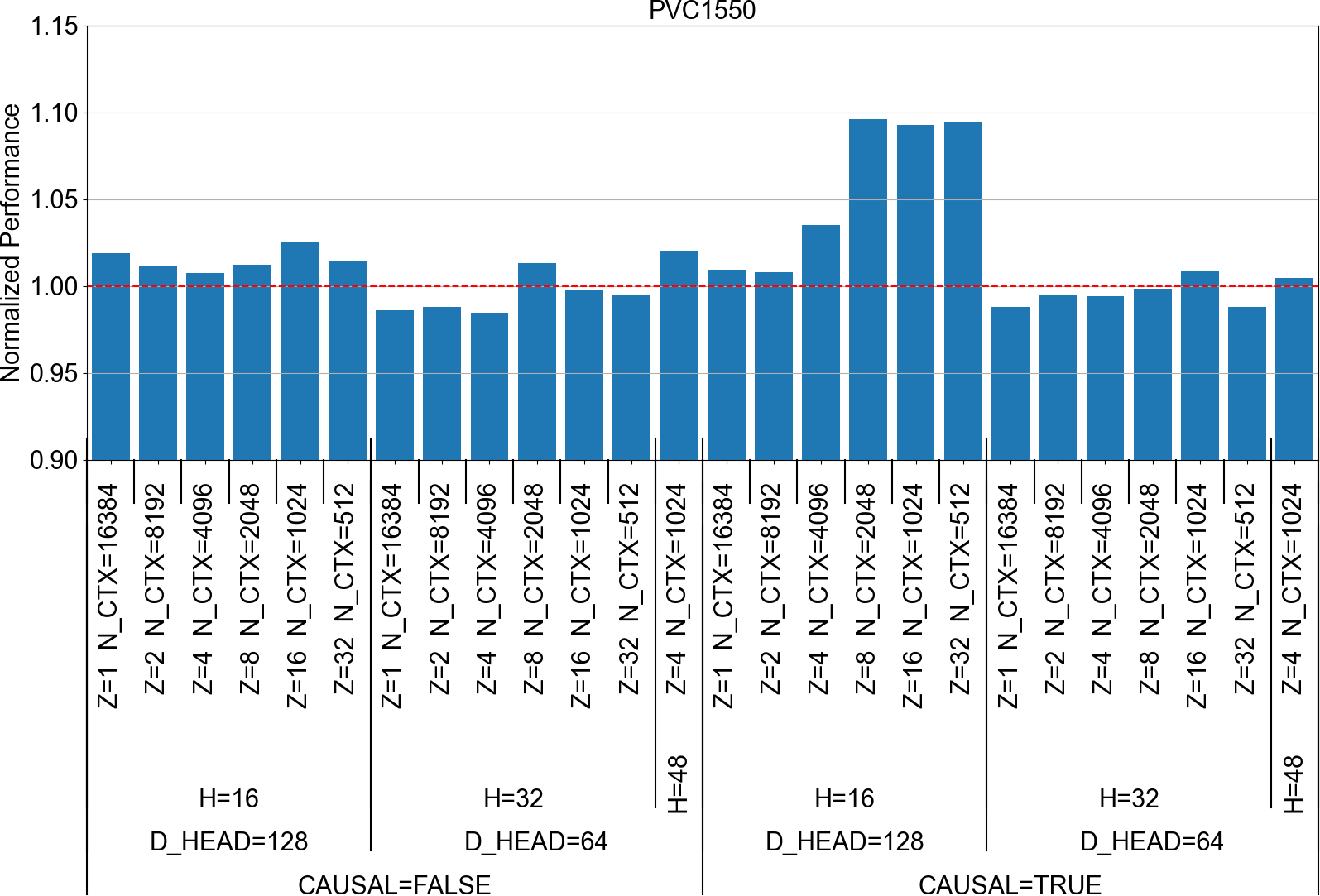

Performance improvement

We have evaluated the performance of Triton FlashAttention v2 on Intel GPU Max PVC. The following plots show the normalised performance of the FlashAttention kernel with the reduce-liveness-pass enabled for different input configurations.

FlashAttention v2 Normalized performance PVC1100

FlashAttention v2 Normalized performance PVC1100

FlashAttention v2 Normalized performance PVC1550

FlashAttention v2 Normalized performance PVC1550

The testbed used for these evaluations and a disclaimer can be found at the bottom of this blog post.

We can see that the pass has improved the performance for several configurations on all the targets evaluated by more than 5%, and up to 10% for some of them. As expected the inputs configurations impacted by this optimisation are those with :

- causal mask applied to the computed data

- D_HEAD=128, which corresponds to a large shape for the Q matrix on the dimension that is not split between warps.

Another point to notice is that GPU target with a smaller compute capacity (and especially a smaller register file) are more impacted by this optimisation. Indeed, only 3 configurations are significantly improved by the pass for PVC1550, which is the best-performing of the PVC GPUs evaluated, whereas on PVC1100, more configurations have been significantly improved.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we showed the importance of taking resource limitations into account, and in particular the limited size of the register file, to generate highly optimised code.

We also exposed that low-level compilers may lack some knowledge about the source code, which can prevent them from generating optimised code. In our use case, the igc compiler tried to assign registers based on the lifespan of the variables without knowing that the lifespan of some variables could be reduced to avoid register spilling. Consequently, we take advantage of the progressive lowering of MLIR-based compilers to add an optimisation pass to the intel XPU backend of the Triton compiler. This pass aims to reduce the liveness of variables under certain conditions. As a result, the performance of FlashAttention could be improved by up to 10% fo certain input configurations.

A limitation of this pass is that we assume the data to be loaded is available in the L1 cache, so the load operations

are cheap and can be easily moved around in the code.

However, this might not be the case if cache conflicts occurred and the data was evicted from the cache before being

loaded into registers. This is likely to happen for GPUs with small cache. If this happens, the load operation becomes

expensive and sinking a loadOp inside the loop body is far from a good idea.

A future extension of the pass could therefore consider first loading the data into the SMEM, which is explicitly

managed by the software, and then loading the data from the SMEM into registers instead of relying on the cache.

Disclaimer*

Experiments performed on 18/07/2025 by Codeplay, with Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 5418Y, Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS, Linux kernel 5.15, Level-zero driver version 1.21.9.0 and IGC compiler Agama version 1146.

Triton Intel XPU backend version 17/07/2025 git commit 288599ed6cbfe616ebbbf35d0fac391821e71daf and Pytorch git

commit 1f57e0e04da9d334e238cec346f7ae3667bed9d1 were used for the performance evaluation.

Performance varies by use, configuration and other factors. Performance results are based on testing as of dates shown in configurations and may not reflect all publicly available updates. See backup for configuration details. No product or component can be absolutely secure. Your costs and results may vary. Intel technologies may require enabled hardware, software or service activation. Intel, the Intel logo, Codeplay and other Intel marks are trademarks of Intel Corporation or its subsidiaries. Other names and brands may be claimed as the property of others.