SYCL Runtime Compilation: A Look Behind the Scenes

20 August 2025

In our previous blog post, we showcased SYCL

runtime compilation (SYCL-RTC) as a powerful new tool for kernel specialisation from a user perspective. In this

article, we explore what actually happens when the application calls

the sycl::ext::oneapi::experimental::build(...)

function in the DPC++ implementation, and why we built it that way. It is also a tale of how modular compiler

technology allowed us to deliver a faster and more secure in-memory compilation pipeline in just a couple months.

For additional context, also check out our talk Fast In-Memory Runtime Compilation of SYCL Code at IWOCL 2025: Slides Video Recording

SYCL-RTC refresher

SYCL-RTC means using

the kernel_compiler

extension to wrap a SYCL source string comprised of kernel definitions in

the free-function syntax

into a kernel_bundle in the ext_oneapi_source state, which is then compiled into exectuable state by the

extension’s build(...) function.

#include <sycl/sycl.hpp>

namespace syclexp = sycl::ext::oneapi::experimental;

// ...

std::string sycl_source = R"""(

#include <sycl/sycl.hpp>

extern "C" SYCL_EXT_ONEAPI_FUNCTION_PROPERTY((

sycl::ext::oneapi::experimental::nd_range_kernel<1>))

void vec_add(float* in1, float* in2, float* out){

size_t id = sycl::ext::oneapi::this_work_item::get_nd_item<1>()

.get_global_linear_id();

out[id] = in1[id] + in2[id];

}

)""";

sycl::queue q;

auto source_bundle = syclexp::create_kernel_bundle_from_source(

q.get_context(), syclexp::source_language::sycl, sycl_source);

// Read on to learn what happens in the next line!

auto exec_bundle = syclexp::build(source_bundle);

But what happens in the background, and how does the SYCL runtime turn your SYCL code into an executable kernel when you

call build(...)? These are the questions that we want to answer throughout the rest of this blog post.

An early prototype

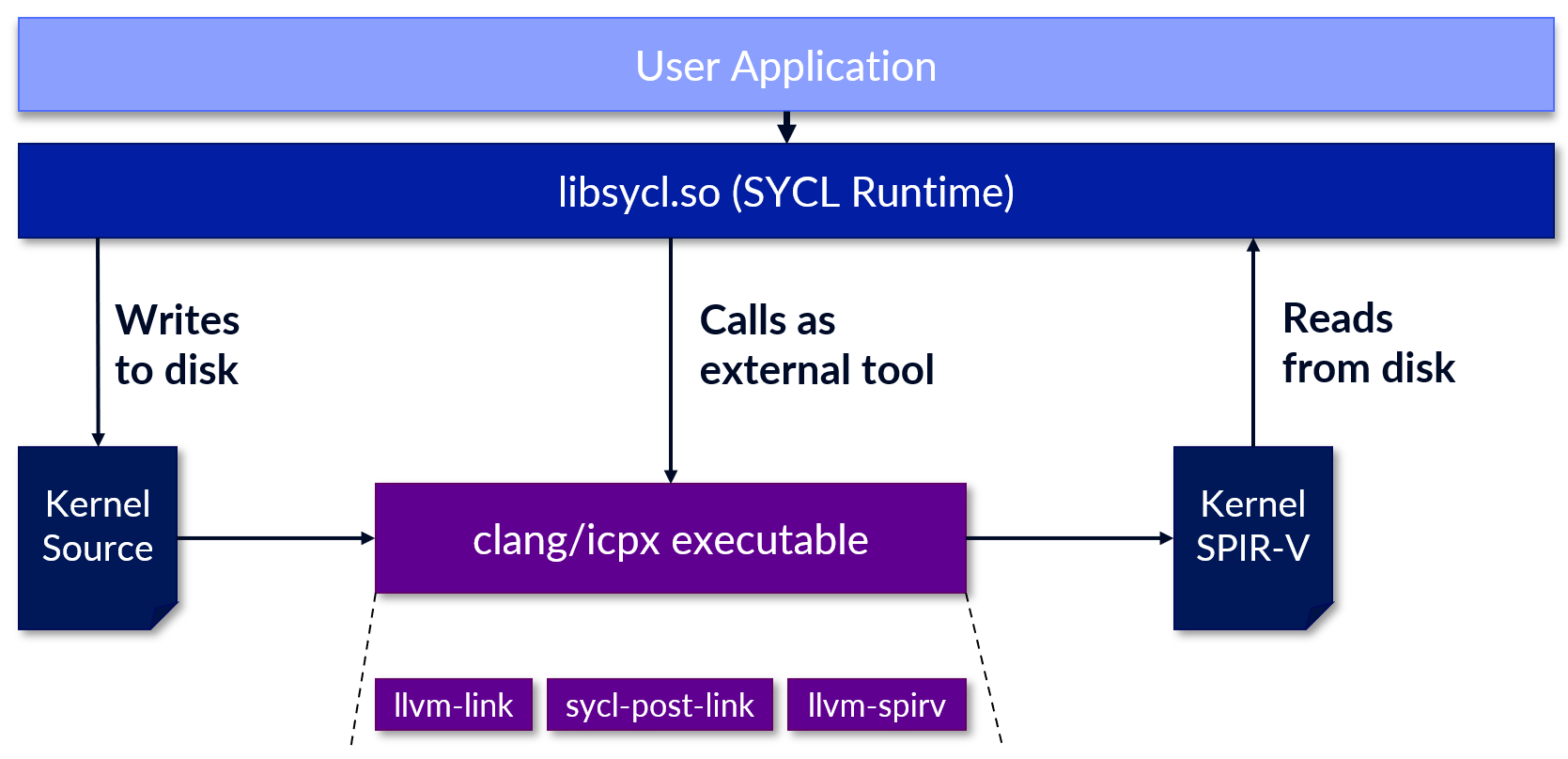

Our first implementation

of the build(...) function wrote the source string into a temporary file, invoked DPC++ on it in a special mode that

dumped the device code to another file in SPIR-V format, and finally loaded that file back into the runtime, from where

it was executed. The following figure shows the pipeline.

The DPC++ compiler is built on top of LLVM and its C/C++ frontend Clang. Internally, the compiler driver orchestrates

the compilation of a SYCL code across multiple tools, connected by intermediate files in a temporary directory. While

enthusiasts can find additional information here,

for understanding the rest of this post it is sufficient to know that device code is extracted and compiled by the

SYCL-enabled frontend to LLVM’s intermediate representation, linked with various device libraries (llvm-link in the

figure), and post-processed by a mix of SYCL-specific transformation passes (sycl-post-link) before finally being

translated into the target format, i.e. SPIR-V when targeting Intel devices (llvm-spirv).

The rationale for an in-memory compilation pipeline

Invoking the DPC++ executable as outlined in the previous section worked reasonably well to implement the

basic kernel_compiler extension, but we observed several shortcomings:

- Functional completeness: Emitting a single SPIR-V file is sufficient for simple kernels, but more advanced device code may result in multiple device images comprised of SPIR-V binaries and accompanying metadata (runtime properties) that needs to be communicated to the runtime.

- Robustness: Reading multiple dependent files from a temporary directory can be be fragile.

- Performance: Multiple processes are launched by the compiler driver, and file I/O operations have a non-negligible overhead.

- Security: Reading executable code from disk is a security concern, and users of an RTC-enabled application may be unaware that a compilation writing intermediate files is happening in the background.

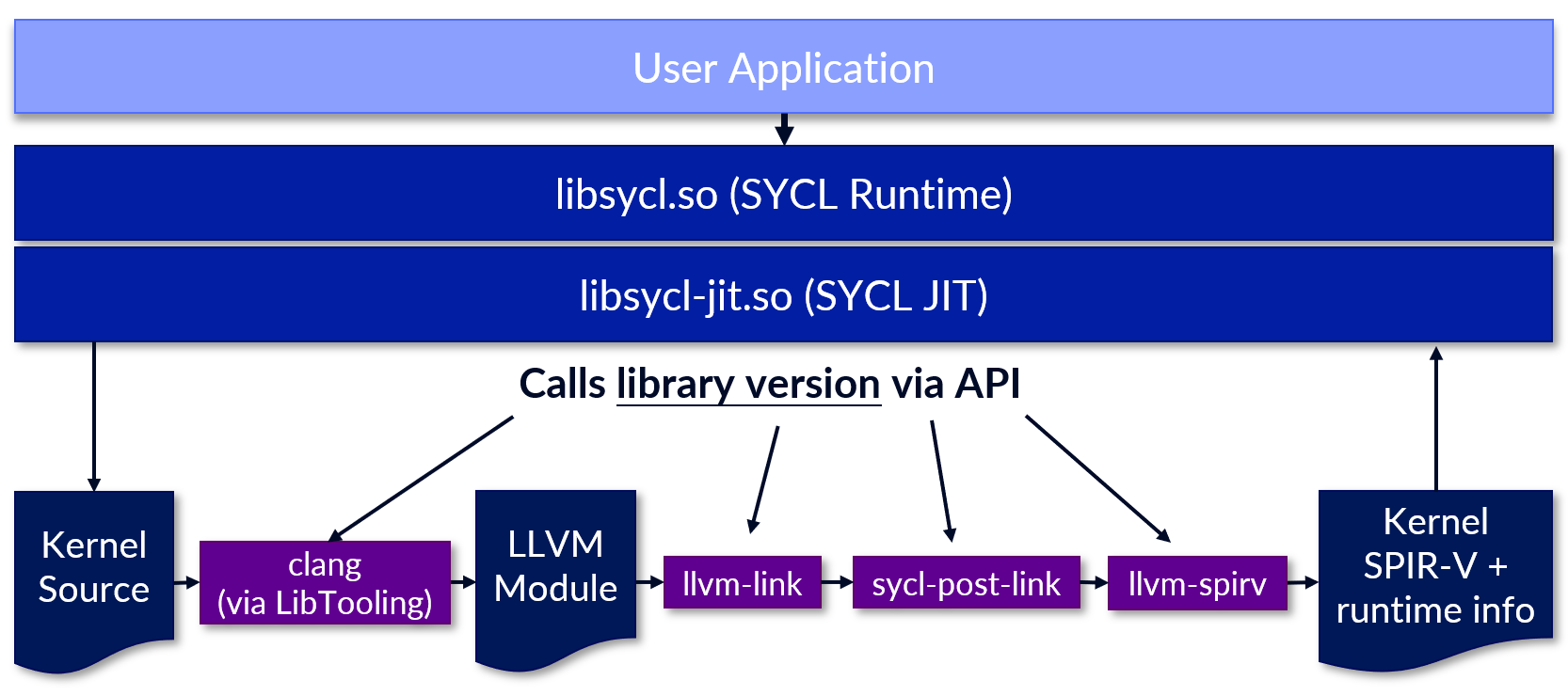

These challenges ultimately motivated the design of the in-memory compilation pipeline that is shown below and is

now the default approach in DPC++ and the oneAPI product distribution since the 2025.2 release. This new approach

leverages modular compiler technology to produce a faster, more feature-rich, more robust and safer implementation

of the kernel_compiler extension.

The individual steps in the pipeline are now invoked programmatically via an API inside the same process, and

intermediate results are passed along as objects in memory. Our implementation is part of the open-source DPCPP++

repository intel/llvm on GitHub, so you can find the code in

the compileSYCL(...)

function. Let’s dive into more detail the following sections!

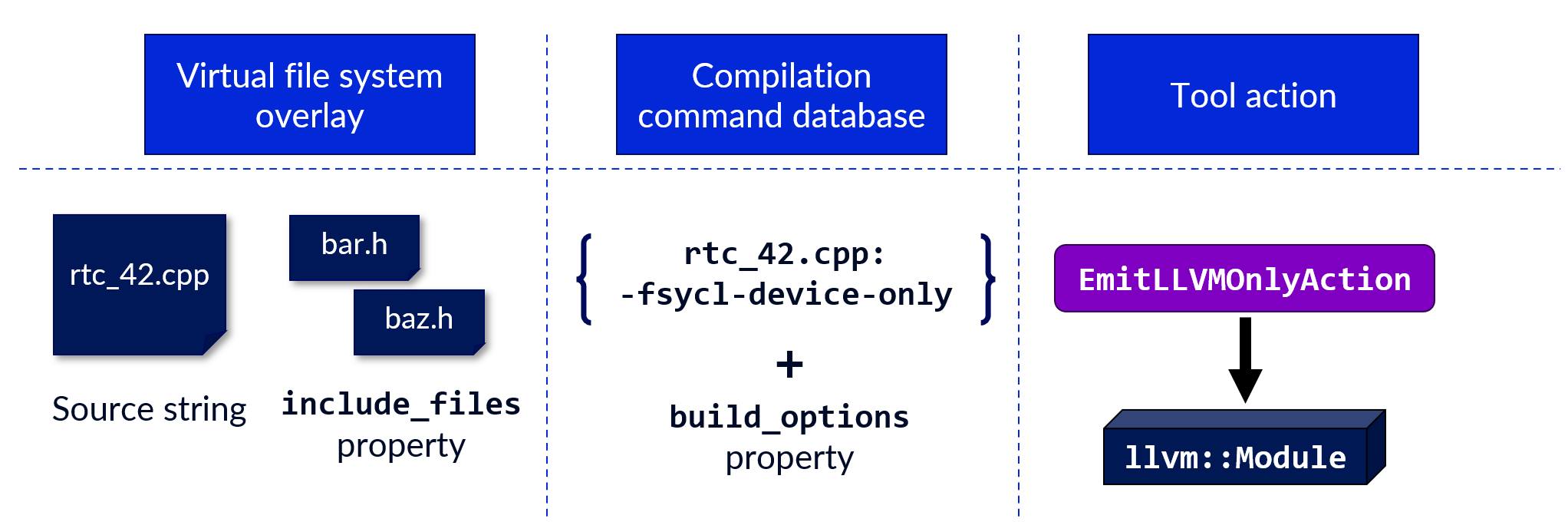

Using the LibTooling API to compile the source string to an llvm::Module

LibTooling is a high-level API to write standalone tools based on Clang,

such as linters, refactoring tools or static analysers. To use it, one defines a tool action to run on a set of files

in a virtual filesystem overlay, which the frontend then processes according to a compilation command database. The

following figure outlines how we map a compilation request originating from the kernel_compiler extension to this API.

This might be a slightly unusual way to use of LibTooling, but we found it works great for SYCL-RTC. Let me show you how

in this section by walking

through jit_compiler::compileDeviceCode(...)

function.

Step 1: Determine the path of the compiler installation

To set up up working frontend invocation, we need to know where to find supplemental files such as the SYCL headers.

Normally, these paths are determined relative to the compiler executable (e.g. clang++ for the open-source DPC++),

however in our case, the executable is actually the RTC-enabled application, which can reside in an arbitrary location.

Instead, we use OS-specific logic

inside getDPCPPRoot()

to determine the location of the shared library sycl-jit.so (or .dll on Windows) which contains the SYCL-RTC

implementation. From its location, we can derive the compiler installation’s root directory.

Step 2: Collect command-line arguments

The next step is to collect the command-line arguments for the frontend invocation.

The adjustArgs(...)

function relies on Clang’s option handling infrastructure to set the required options to enter the device compilation

mode (-fsycl-device-only), set up the compiler environment, and select the target. Finally, any user-specified

arguments passed via

the build_options

property are appended to the list of command-line arguments.

Step 3: Configure the ClangTool

Once we know the required command-line arguments, we can set up the compilation command database and

an instance

of

the ClangTool

class, which provides the entry point to the LibTooling interface. As we’ll be translating only a single file containing

the source string, we construct

a FixedCompilationDatabase

relative to the current working directory.

To implement the kernel_compiler extension cleanly, we need to capture all output (e.g. warnings and errors) from the

frontend.

The ClangDiagnosticsWrapper

class configures

a TextDiagnosticsPrinter

to append all messages to a string maintained by our implementation to collect all output produced during the runtime

compilation.

The configuration of the ClangTool instance continues in

the setupTool

function. First, we redirect all output to our diagnostics wrapper. Then,

we set up the overlay filesystem

with a file named rtc_<n>.cpp (n is incremented for each use of the kernel_compiler extension’s build(...)

function) in the current directory with the contents of the source string. Each of the virtual header files that the

application defined via

the include_files

property becomes also a file in the overlay filesystem, using the path specified in the property.

The ClangTool class exposes so-called argument adjusters, which are intended to modify the command-line arguments

coming from the compilation command database. We have

to clear

the default adjusters defined by the class, because one of them injects the -fsyntax-only flag, which would conflict

with the -fsycl-device-only flag we need for SYCL-RTC. Finally,

we add

an argument adjuster ourselves to overwrite the name of executable in the invocation. Again, this is to help the correct

detection of the environment, by making the invocation as similar as possible to a normal use of DPC++.

Step 4: Run an action

The last step is to define

a ToolAction

to be executed on the source files. Clang conveniently provides

the EmitLLVMAction,

which runs the frontend up until the LLVM IR code generation, which is exactly what we need. However, LibTooling does

not provides a helper to wrap it in a ToolAction, so we need to define and run our

own GetLLVMModuleAction.

We extracted common boilerplate code to configure

a CompilerInstance

in

the RTCActionBase

class. Inside the GetLLVMModuleAction, we instantiate and execute the aforementioned EmitLLVMAction, and, in case

the translation was

successful, obtains ownership

of the constructed llvm::Module from it.

Finally, the call

to Action.takeModule()

transfers ownership again to the caller of compileDeviceCode. Note that this simple mechanism works because we know

that there is only a single compilation happening for every instance of the ClangTool and hence

our GetLLVMModuleAction class.

Caching

In our previous blog post, we noted that we implemented a persistent cache for the invocation of the frontend, which we observed to be the most expensive (in terms of runtime overhead) phase of our compilation pipeline. Let’s have a closer look how the cache works.

Overall design

We cache only the frontend invocation, meaning that after a successful translation, we store the LLVM IR module obtained via LibTooling on disk in the Bitcode format using built-in utilities. In case of a cache hit in a later runtime compilation, we load the module from disk and feed it into the device linking phase. The rationale for this design was that were no utilities to save and restore the linked and post-processed device images to disk at the time ( the SYCLBIN infrastructure was added later), and caching these steps would have resulted only in marginal further runtime savings.

Cache key considerations

The main challenge is to define a robust cache key. Because code compiled via SYCL-RTC can #include header files

defined via the include_files property as well as from the filesystem, e.g. sycl.hpp from the DPC++ installation or

user libraries, it is not sufficient to look only at the source string. In order to make the cache as conservative as

possible (cache collisions are unlikely but mathematically possible), we decided to compute a hash value of the

preprocessed source string, i.e. with all #include directives resolved. We additionally compute a hash value of the

rendered command-line arguments, and append it to the hash of the preprocessed source to obtain the final cache key.

Implementation notes

The cache key computation is implemented in

the jit_compiler::calculateHash(...)

function. We are again relying on LibTooling to invoke the preprocessor - handily, Clang provides

a PreprocessorFrontendAction

that we extend to tailor to our use-case.

We choose BLAKE3 as the hash algorithm because its proven in

similar contexts (most notably, ccache) and available as a utility in the LLVM ecosystem. As the

output is a byte array, we apply Base64 encoding to obtain a character string for use with the persistent cache.

Device library linking and SYCL-specific transformations

With an LLVM IR module in hand, obtained either from the frontend or the cache, the next steps in the compilation pipeline are simple (at least for compiler folks 😉). As these steps are mostly SYCL-specific, we won’t go into as much detail as in the previous section.

The device library linking is done by

the jit_compiler::linkDeviceLibraries(...)

function. These libraries provide primitives for a variety of extra functionality, such as an extended set of math

functions and support for bfloat16 arithmetic, and are available as Bitcode files inside the DPC++ installation or the

vendor toolchain, so we just use LLVM utilities to load them into memory and link them to the module representing the

runtime-compiled kernels.

For the SYCL-specific post-processing, implemented

in jit_compiler::performPostLink(...),

we can reuse modular analysis and transformation passes in

the SYCLLowerIR component. The main tasks for the

post-processing passes is to split the device code module into smaller units (either as requested by the user, or

required by the ESIMD mode), and to compute the properties that need to be passed to the SYCL runtime when the device

images are loaded.

Translation to the target format

The final phase in the pipeline is to translate the LLVM IR modules resulting from the previous phase into a device-specific target format that can be handled by the runtime. For Intel CPUs and GPUs, that’s binary SPIR-V. For AMD and NVIDIA GPUs, we emit AMDGCN and PTX assembly, respectively. Over time, we created our own set of utilities to facilitate the translation. Internally, we dispatch the task to either the SPIR-V translator (a copy of which is maintained inside the DPC++ repository), or use vendor-specific backends that are part of LLVM to generate the third-party GPU code.

New hardware support

You might be surprised that we talked about target formats for AMD and NVIDIA GPUs in the previous paragraph - in our

IWOCL talk, we still said that SYCL-RTC only works on Intel hardware. Well, that is another exciting bit of news that we

can share in this blog post: We have recently enabled support for SYCL-RTC on AMD and NVIDIA GPUs! The usage of

the kernel_compiler extension remains the same for SYCL devices representing such a third-party GPU. The concrete GPU

architecture is queried via the environment variable SYCL_JIT_AMDGCN_PTX_TARGET_CPU when executing the RTC-enabled

application. For AMD GPUs, it is mandatory to set it. For NVIDIA GPUs, it is highly recommended to change it from

the conservative default architecture (sm_50).

$ clang++ -fsycl myapp.cpp -o myapp

$ SYCL_JIT_AMDGCN_PTX_TARGET_CPU=sm_90 ./myapp

A list of values that can be set as the target CPU can be found in

the documentation of the -fsycl-targets= option (

leave out the amd_gpu_ and nvidia_gpu_ prefixes).

At the moment, the support is available in daily builds of the open-source version of DPC++.

Conclusion

Thanks for reading on until here! As you can see, our approach to SYCL-RTC is built as a clever combination over existing components and utilities. To recap, we leverage:

- DPC++’s SYCL-extended Clang version via LibTooling to preprocess and compile SYCL device code

- LLVM utilities for reading and writing Bitcode files

- LLVM utilities for computing the BLAKE3 hash value and a Base64 encoding of the result

- SYCL-specific passes for post-processing

- SPIR-V translator, as well as the LLVM backends for AMD and NVIDIA GPUs

It is clear that without the prevalence of modular design practices in modern compilers, shipping the in-memory pipeline in a just a few months would have been impossible. An additional soft benefit is that reusing as much as possible of the existing codebase minimises differences and user surprises between “normal” and runtime compilation.

The team behind SYCL-RTC

The work presented in this blog post is a joint effort by

- Julian Oppermann, Lukas Sommer and Jakub Chlanda at Codeplay Software, and

- Chris Perkins, Steffen Larsen, Alexey Sachkov and Greg Lueck at Intel.