Simulating Crowd Simulation with SYCL

21 December 2022

In 1995, Dirk Helbing introduced the Social Force Model for Pedestrian Dynamics, aimed at modelling the behavior of crowds using Langevin equations [1]. He proposed a refined model in a 2000 paper “Simulating Dynamical Features of Escape Panic” [2]. The world’s first commercially available GPU came to market four years after the publication of Helbing’s initial paper and changed the landscape of computing. Heavy workloads such as the one outlined by Helbing could now be offloaded to the GPU and processed in parallel. The goal of this blog post is to demonstrate how SYCL can be used to develop efficient and performance portable implementations of computationally intensive models, using the Social Force Model to illustrate.

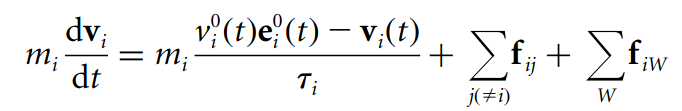

The Model

Helbing suggests that human behavior in large crowds is determined by three component forces: a personal impulse towards one’s destination, the cumulative force exerted by neighboring people and the repulsive force from any nearby walls. Together, these forces form the basis of the differential equation below, which can subsequently be integrated in order to calculate the person’s velocity.

Here is the same equation written in plain English:

Helbing’s model is akin to a particle system such as an N-body simulation, however physical forces are replaced by psycho-social impulses. What results is an environment where individuals are drawn towards their destinations, whilst avoiding getting too close to other individuals and walls.

With an intuitive understanding of Helbing’s model, we can begin to consider how we should go about parallelizing such a system. 2D graphics will be rendered using SDL. Alongside the simulation itself, it will be useful to collate statistics from the model.

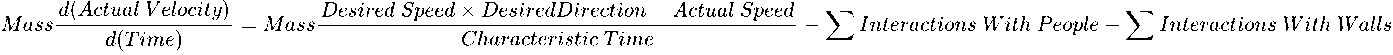

There are three main instances of parallelism in this project, each of which maps to a separate kernel:

- Given the number of calculations it requires, we can assume that the most computationally intensive kernel will involve the calculation of actor velocities. Each actor will occupy a separate SYCL work-item

- Actor bounding boxes will be updated in parallel

- Recording and summarizing the statistics will use kernels to check actor statuses at each timestep and reduction kernels for calculating averages

Crowd simulation on the GPU is not a compute-bound process; the calculations being carried out aren’t too costly and it lends itself well to SIMD architecture. Instead, the main performance bottleneck comes from memory transfers. Thus, a key design consideration is how to minimize the amount of time the GPU spends idle whilst waiting for costly data transfers to complete.

The Main Kernel

The focal point of the model is calculating actor forces in the function differentialEq. differentialEq is called in

parallel for each actor at every timestep for as long as the simulation is running. This means that each call to

differentialEq occupies a single work-item which maps to a single core on the GPU. The GPU can execute separate

threads on separate cores simultaneously; this is the essence of parallelism in computing. In our implementation

geometric vectors (denoting actor positions, velocities, etc.) are implemented as sycl::float2 variables because

SYCL defines vector and SIMD mathematical operations on these types. The differentialEq kernel is invoked in the

following manner:

myQueue.submit([&](sycl::handler &cgh) {

// Create accessors for accessing data on the device

auto actorAcc =

actorBuf.get_access<sycl::access::mode::read_write>(cgh);

auto wallsAcc = wallsBuf.get_access<sycl::access::mode::read>(cgh);

auto pathsAcc = pathsBuf.get_access<sycl::access::mode::read>(cgh);

auto heatmapEnabledAcc =

heatmapEnabledBuf.get_access<sycl::access::mode::read>(cgh);

cgh.parallel_for(

sycl::range<1>{actorAcc.size()}, [=](sycl::id<1> index) {

if (!actorAcc[index].getAtDestination()) {

differentialEq(index, actorAcc, wallsAcc,

pathsAcc, heatmapEnabledAcc);

}

});

});

A crucial point to note is that ordinarily SYCL kernels cannot call functions from different translation units. Doing so will cause a compile time error informing us that the function in question is not defined within the scope of the kernel’s translation unit. In DPC++ this can be resolved by adding the macro SYCL_EXTERNAL to your function declarations. SYCL_EXTERNAL enables external linkage for all functions called on the device. SYCL_EXTERNAL is marked as optional in the SYCL specification so not all SYCL implementations are guaranteed to support it. In such cases, any functions called from within a kernel must be declared in the same header file as the kernel itself to ensure that they both end up in the same translation unit. differentialEq begins by calculating each actor’s personal impulse towards their destination:

// Calculate personal impulse

float mi = currentActor->getMass(); // Actor mass

float v0i = currentActor->getDesiredSpeed(); // Desired speed

sycl::float4 destination =

paths[currentActor->getPathId()]

.getCheckpoints()[currentActor->getDestinationIndex()];

// Find direction vector to nearest point in destination region

std::pair<float, sycl::float2> minRegionDistance;

std::array<sycl::float2, 4> destinationRect = {

sycl::float2{destination[0], destination[1]},

sycl::float2{destination[2], destination[1]},

sycl::float2{destination[2], destination[3]},

sycl::float2{destination[0], destination[3]}};

for (int x = 0; x < 4; x++) {

int endIndex = x == 3 ? 0 : x + 1;

auto dniw =

getDistanceAndNiw(currentActor->getPos(),

{destinationRect[x], destinationRect[endIndex]});

if (dniw.first < minRegionDistance.first || minRegionDistance.first == 0) {

minRegionDistance = dniw;

}

}

minRegionDistance.second = normalize(minRegionDistance.second);

sycl::float2 e0i = {-minRegionDistance.second[0], // Desired direction

-minRegionDistance.second[1]};

sycl::float2 vi = currentActor->getVelocity(); // Actual velocity

sycl::float2 personalImpulse = mi * (((v0i * e0i) - vi) / Ti);

// Ti is a constant denoting the “characteristic time”

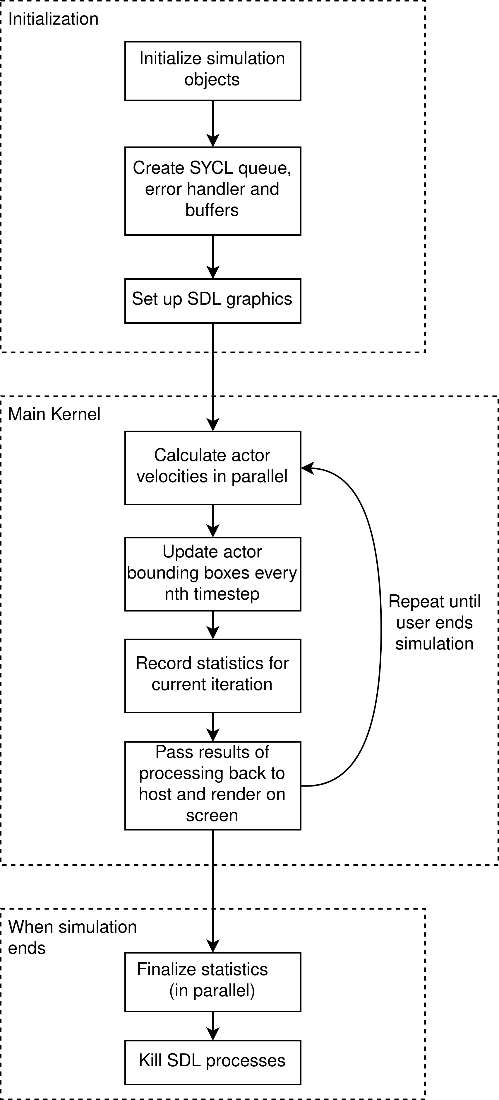

Ultimately, this is a fairly simple calculation with the most expensive operation being the calculation of the direction vector for the nearest point to the actor in the destination region (this is required because destinations are defined as rectangular regions rather than points). Once personal impulse has been calculated, the next step is to calculate the cumulative force exerted by neighboring actors. An early optimization we deemed necessary was the implementation of bounding boxes. The space in which the simulation takes place is split up into a grid, with each actor having an attribute for the box it belongs to. When calculating neighbor forces, only actors in the current actor’s bounding box and the 8 perimeter boxes are considered, operating on the assumption that an actor further away from the current actor is not likely to exert a force on them. Each actor’s bounding box is updated in parallel every 20th timestep.

// Update actor bounding boxes

myQueue.submit([&](sycl::handler &cgh) {

auto actorAcc = actorBuf.get_access<sycl::access::mode::read_write>(cgh);

cgh.parallel_for(sycl::range<1>{actorAcc.size()}, [=](sycl::id<1> index) {

Actor *currentActor = &actorAcc[index];

sycl::float2 pos = currentActor->getPos();

int row = sycl::floor(pos[0]);

int col = sycl::floor(pos[1]);

currentActor->setBBox({row, col});

});

});

myQueue.throw_asynchronous();

This is not an optimal bounding box implementation and is something that could be revisited. Storing data as an attribute of the Actor class means that there are no performance benefits from coalesced memory accesses. An optimal implementation would involve maintaining a list of actors in each bounding box. The issue with this approach is that the lists for each bounding box should be dynamic in size, but SYCL can only use static containers in kernels. This could possibly be circumvented by a linked list of pointers, although this enforces serial access which diminishes performance on the GPU. That being said, even the current suboptimal implementation led to a 29% decrease in execution time when running benchmarks.

Neighboring forces are calculated for each actor in the following manner, using bounding boxes to reduce the number of calculations required:

// Calculate forces applied by neighbouring actors (in valid bounding boxes)

sycl::float2 peopleForces = {0, 0};

for (int x = 0; x < actors.size(); x++) {

Actor neighbour = actors[x];

bool bBoxFlag = std::any_of(neighbourBoxes.begin(), neighbourBoxes.end(),

[neighbour](std::array<int, 2> i) {

return i[0] == neighbour.getBBox()[0] &&

i[1] == neighbour.getBBox()[1];

});

if (actorIndex != x && !neighbour.getAtDestination() && bBoxFlag) {

// Direction vector from actor to neighbour

sycl::float2 currentToNeighbour = pos - neighbour.getPos();

// Distance between actor and neighbour

float dij = magnitude(currentToNeighbour);

// Combined radius

float rij = neighbour.getRadius() + currentActor->getRadius();

// Normalized direction vector

sycl::float2 nij = currentToNeighbour / dij;

// Tangential direction vector

sycl::float2 tij = getTangentialVector(nij);

float g = dij > rij ? 0 : rij - dij;

float deltavtij = dotProduct(

(neighbour.getVelocity() - currentActor->getVelocity()), tij);

peopleForces += (PEOPLEAi * sycl::exp((rij - dij) / Bi) + K1 * g) * nij +

(K2 * g * deltavtij * tij);

}

}Repulsive forces from walls are calculated after neighbor forces. This requires some involved vector maths to do with finding the nearest point on a line to an actor. The helper functions used here are defined in MathHelper.cpp.

// Calculate forces applied by walls

sycl::float2 wallForces = {0, 0};

for (int x = 0; x < walls.size(); x++) {

std::array<sycl::float2, 2> currentWall = walls[x];

float ri = currentActor->getRadius();

// Distance to wall and normalized direction vector

std::pair<float, sycl::float2> dAndn = getDistanceAndNiw(pos, currentWall);

float diw = dAndn.first;

float g = diw > ri ? 0 : ri - diw;

sycl::float2 niw = normalize(dAndn.second);

// Tangential direction vector

sycl::float2 tiw = getTangentialVector(niw);

wallForces += (WALLAi * sycl::exp((ri - diw) / Bi) + K1 * g) * niw -

(K2 * g * dotProduct(vi, tiw) * tiw);

}An adaptation I made to Helbing’s model was the introduction of random variations in force to lend the simulation more of that unpredictability one observes in real life crowds. The implementation details are discussed in the next section. Actors can also be colored according to the social force they are experiencing, generating a heatmap which helps visualize where forces are at their most intense across the crowd; an important feature for modelling emergency evacuation scenarios and something we inadvertently found very useful for debugging purposes. Once the forces have been accumulated and the variations have been applied, the last step is to integrate the result using a fixed timestep and check if the actor has reached its destination.

// Perform integration

sycl::float2 acceleration = forceSum / mi;

currentActor->setVelocity(vi + acceleration * TIMESTEP);

currentActor->setPos(pos + currentActor->getVelocity() * TIMESTEP);

currentActor->checkAtDestination(

destination, paths[currentActor->getPathId()].getPathSize());

Random Number Generation on the GPU

Standard library random number generators can’t be invoked from the device. Intel’s oneMKL library provides efficient

RNGs for SYCL, however in the spirit of learning new things, I decided to implement my own XOR shift RNG based on a

paper by George Marsaglia [3]. XOR shift generators are random enough to achieve the desired

effect in this

particular use case and are fast enough to not cause significant overhead. Each actor’s RNG is seeded on the host

using std::uniform_int_distribution during initialization.

Below is my implementation of a XOR shift pseudo-random number generator:

// xorshift RNG developed by George Marsaglia

// https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/download/v008i14/916

SYCL_EXTERNAL uint randXorShift(uint state) {

state ^= (state << 13);

state ^= (state >> 17);

state ^= (state << 5);

return state;

}

Gathering Statistics

Statistic collation is split into two functions:

updateStatsis called each timestep and records the average force applied to actors, the execution time of that iteration, and the time it takes for any actor to reach their destination if they have done so during that timestepfinalizeStatsis called at the end of execution and calculates the average kernel duration before writing the results to a text file

Results can be used to generate graphs by running GenerateGraphs.py. Both functions use reduction kernels – a feature introduced in SYCL 2020 which saves developers from having to implement their own parallel reductions by hand.

// Calculate average kernel duration using reduction kernel

myQueue.submit([&](sycl::handler& cgh) {

auto durationAcc =

kernelDurationsBuf.get_access<sycl::access::mode::read>(cgh);

auto sumReduction = sycl::reduction(durationSumBuf, cgh, sycl::plus<int>());

auto out = sycl::stream{64, 1028, cgh};

cgh.parallel_for(

sycl::range<1>{durationAcc.size()}, sumReduction,

[=](sycl::id<1> index, auto& sum) { sum += durationAcc[index]; });

});Optimizations and Lessons Learnt

Developing this project was an iterative process. The first version underwent many improvements and performance optimizations before getting to its current state. This process involved using profiling tools such as Intel's VTune and NVIDIA Nsight Systems as well as expanding my understanding of the theoretical nuances of GPU programming.

One of the most common operations carried out in the main kernel is vector normalization. Calculating square roots is

a costly operation which introduces lots of overhead when used frequently to normalize vectors. A colleague pointed

me in the direction of the “Fast Inverse Square Root” optimization; a way of quickly calculating the inverse square

root using numerical methods discovered by the developers of first-person shooter Quake III. SYCL has its own method

for calculating the inverse square root - sycl::rsqrt. Using this optimization resulted in a 2.63% decrease in

execution time.

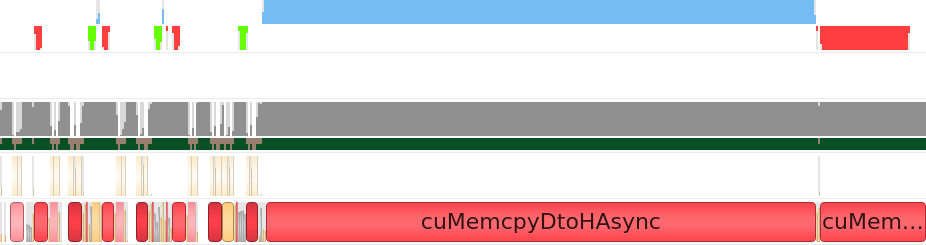

It was mentioned earlier that we are dealing with a memory-bound system as opposed to a compute-bound one. When using Nsight Systems to profile performance on the CUDA backend, it became apparent that substandard memory access patterns were being used. Below is the initial nsys output for one iteration (includes bounding box updates):

The nsys output shows that too many memory transfers are taking place. We have these small blue kernels visible in

the top row surrounded by suspiciously symmetrical memory transfer operations in the row below (the green and red

blocks). The two tiny kernels are the kernels which update statistics and change actor bounding boxes and the larger

kernel is the force calculation. The current memory access pattern means that new buffers are created for each

kernel and destroyed after that kernel completes. This creates plenty of unnecessary overhead as buffer creation and

deletion is an expensive operation, particularly deletion blocks which have to wait until the data is transferred

from the device back to the host. Data only needs to be copied to and from the device once per iteration; it should

stay on the device between each kernel and should only be relayed back to the host when we need to render the

results of processing on screen. The revised approach is to create the buffers once during initialization, copy

their contents onto the device once at the start of each iteration and then use a sycl::host_accessor to access data

on the device when required. This produced the following nsys output:

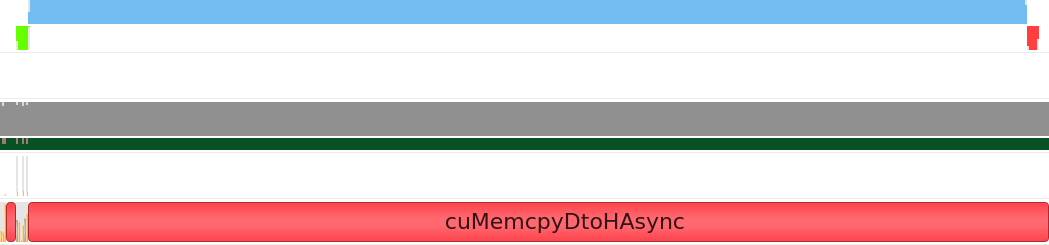

If we look once more at the top two rows of this output, we can see one green block showing the copy operation from

the host to the device, then the three kernels are executing back-to-back without having to wait for unnecessary

memory transfers, and finally the data is copied back to the host when the host_accessor is created. Because the

same buffers are being reused, all data remains on the device between kernels unless we explicitly request access to

it through the creation of a host_accessor.

At the end of every queue submission, I had initially called queue.wait_and_throw. This causes a blocking operation whilst the program waits for all queue operations to complete and throws any runtime errors. However, when using SYCL’s buffer/accessor model, it is not advised to wait after every command. Instead, you should allow the SYCL runtime to create dependencies between kernels. SYCL supports implicit data movement for buffers, meaning that the SYCL runtime infers dependencies and data movement from the access requirements of command groups. For example, if buffer A is changed in kernel 1 and then used in kernel 2, the SYCL runtime knows to wait until kernel 1 has finished with buffer A before moving on to kernel 2, hence eliminating the need to explicitly call wait on a queue. These calls to wait_and_throw can therefore be replaced with throw_asynchronous.

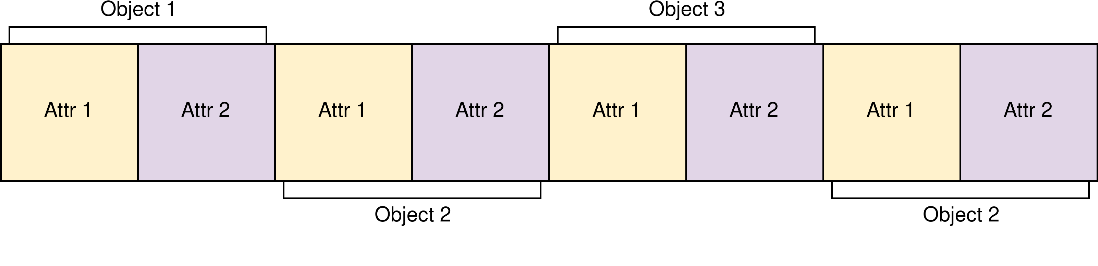

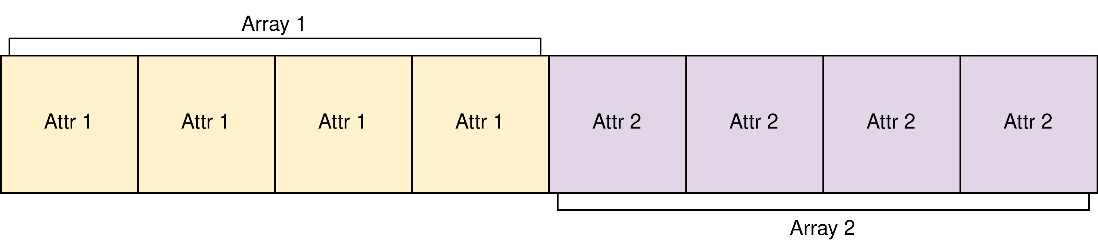

One of the most fundamental design mistakes I made during this project and what went on to be the cause of the greatest performance bottleneck was adopting to use an array of structs (AoS) layout instead of struct of arrays (SoA) for my main actor class. When a GPU accesses global memory, it accesses blocks of memory instead of single memory addresses. Hence, the way data is arranged in memory may have an effect on performance. If we use a conventional array of structs for storing objects, this is how attributes will be arranged in memory:

And this is what memory will look like if we use a struct of arrays:

Assume that our GPU accesses memory in chunks of 4 blocks. If we wanted to gather all of the values for attribute 1 using AoS, the GPU would require two memory access operations to get all the data it needs. However, using SoA it can fetch everything in one memory access. The general rule of thumb is that accessing data which is physically close together in memory is more efficient because we can make use of coalesced memory accesses. In its current form, the project uses AoS. Transitioning to SoA would likely bring major performance benefits, particularly because it is a memory-bound system, the trade-off being that it would require an entire restructuring of the code.

Results

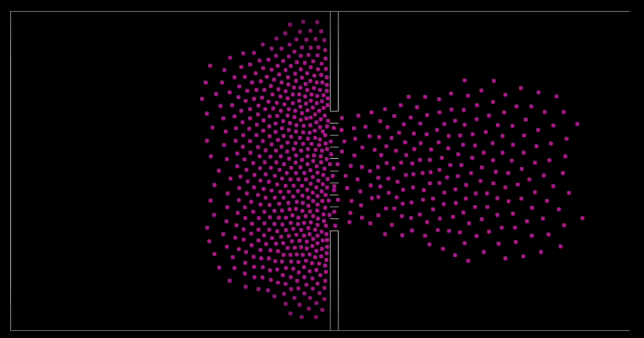

The video above shows two groups of 5000 actors charging into each other. It demonstrates a key phenomenon Helbing observed in his study of crowds and one which he wanted his model to emulate; that being “emergent lane formation.” When two crowds with different destinations meet, actors with the same destination will bunch together into disparate lanes carved out by “leader” actors propelled along by the momentum of the crowd behind them.

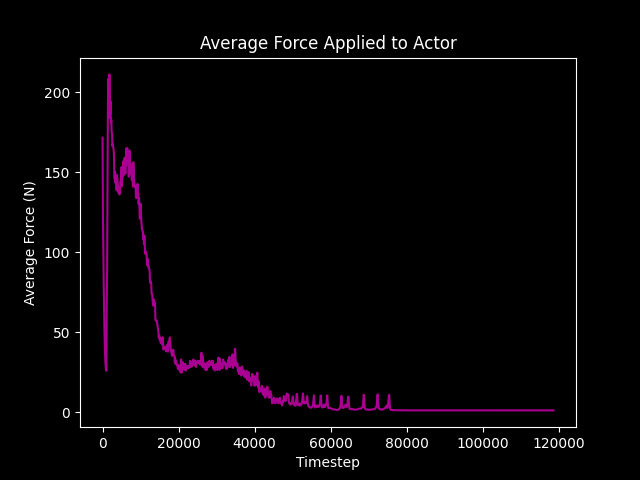

If we take a look at this graph charting the average force applied to each actor during each iteration, we can observe that the average force is at its highest when the two crowds are locked together, and the lanes are being formed. The average force tapers off once the two groups make their way past each other and actors begin to break out of the collision area. You can observe this in the video after the 1:45 mark where the crowd starts losing its density as actors are able to spread out into the available space.

The next simulation shows how crowd simulation algorithms can be used to test building layouts in emergency evacuation scenarios. This environment is modelled after stadium and venue entrances, which often put in place barriers to form lanes for people to siphon through. Splitting the space that the crowd is trying to move through into lanes has the effect of reducing crowd throughput, giving actors more time and space to reach their destination once they have passed the barrier. When the lanes are removed, the crowd reaches its destination much faster, however a large group of unimpeded people converging on the same spot without any barriers to absorb their momentum is fertile ground for injury.

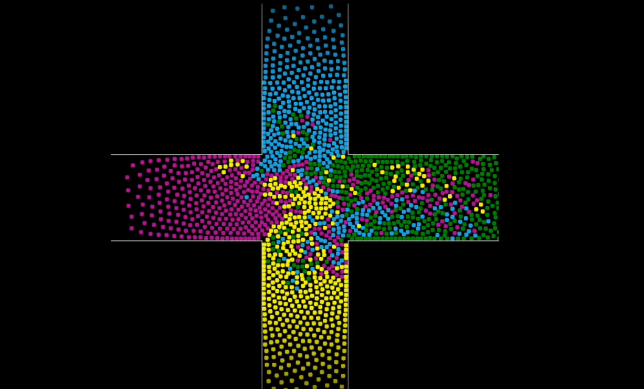

The final example output involves four groups of people colliding at a crossroads. This scenario is a good example of what is termed the “faster is slower effect.” In the above video, the purple crowd has a faster speed than the other three groups. However, I found that giving the purple crowd the same speed as the other groups resulted in the purple crowd arriving at their destination quicker than when they were moving at a faster pace. This is because when all the groups have the same speed, a sort of self-organization begins to emerge whereby groups find a more orderly passage past each other. However, the disruptive force of the purple group when it is given a higher speed undermines this natural order, leading to more frequent deadlocks and standstills.

Portable Code

SYCL enables developers to write portable code without compromising on performance. This project can be compiled for

devices with OpenCL, CUDA or HIP backends. We ran on an Intel Iris XE GPU running OpenCL and a NVIDIA Titan RTX GPU

running CUDA. Two very different devices, one integrated and one discrete. This was run in profiling mode, meaning

that there is no overhead from SDL rendering (this can be activated via the CMake flag –DPROFILING_MODE).

The simulation engine takes a JSON file as an input and uses that to setup the environment and parameters of the simulation. The format this input file should observe is defined in the project README. Example input files are generated by the python script InputFileGenerator.py. It is possible to run these tests with a varying number of actors and iterations, you can run these to see how this affects the kernel execution.

The crowd simulation code can be found in this repository https://github.com/codeplaysoftware/sycl-crowd-simulation.

Citations

- [1] Helbing, Dirk & Molnar, Peter. (1995). Social Force Model for Pedestrian Dynamics. Physical Review E. 51. 10.1103/PhysRevE.51.4282. https://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/9805244

- [2] Helbing, D., Farkas, I. & Vicsek, T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature 407, 487–490 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35035023

- [3] Marsaglia, G. (2003). Xorshift RNGs. Journal of Statistical Software, 8(14), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v008.i14

Notes and Disclaimers

Performance varies by use, configuration and other factors.

Performance results are based on testing as of dates shown in configurations and may not reflect all publicly available updates. See backup for configuration details. No product or component can be absolutely secure.

Your costs and results may vary.

Intel technologies may require enabled hardware, software or service activation.