SYCL for Safety Practitioners – SYCL for Automotive AI and ADAS applications

01 September 2020

SYCL for Safety Practitioners Series

Part 1 - An Introduction

Part 2 - SYCL for Automotive AI and ADAS applications

Part 3 - SYCL ADAS Applications Topology Explained

Introduction

Welcome to the second in my series of technical articles. In the last blog, I introduced this series of technical articles for SYCL™ safety practitioners outlining the benefits for you. In this article, I am going to give you an overview of a typical SYCL application for safety applications. This should give you a good platform upon which you can see the anatomy of the ADAS or AI compute stack unfold. This article is an introduction to SYCL much like other SYCL articles or texts but with a focus on safety.

SYCL Open Standard

You may have already seen this statement or something very much like it when you were first introduced to SYCL:

"SYCL is an open standard specification from the Khronos® group which defines a single source C++ programming layer that allows developers to leverage C++ features on a range of heterogeneous devices. Supported by OpenCL™, it takes advantage of heterogeneous hardware architectures that enable parallel execution on a range of hardware including CPUs, GPUs, and FPGAs, it provides a foundation for creating efficient, portable, and reusable middleware libraries and applications."

It may expand further with:

"SYCL was designed to be a high-level programming layer for OpenCL, and the current SYCL 1.2.1 specification requires OpenCL to be conformant, however, its high-level abstraction means that it's possible to implement non-conformant SYCL on top of virtually any C or C++ based heterogeneous programming model."

But before we delve any further, a quick explanation of how the SYCL implementations ComputeCpp™ by Codeplay™ and Intel's® DPC++ fit into the SYCL programming scene. You may be asking "Are they the same?", "How are they different?". While both implementations are based on the SYCL 1.2.1 specification and therefore share a significant baseline, I will go into greater detail in a future technical article describing the differences between them, as there are some that you need to be aware of. But for now, let's assume they work in the same way, and they can both execute the same code without any modification. Their implementation topology is similar, but their components and concepts go by different names, which can add to some of the confusion. Intel's DPC++ came to be in 2019 and is aimed at High-Performance Compute or HPC as it is more commonly known, while ComputeCpp, which has been around since SYCL's conception way back in 2014 is already being used to target HPC, mobile and autonomous vehicle embedded systems. There is also a new Khronos SYCL 2020 provisional specification, the successor to SYCL 1.2.1, but these articles will concentrate on the 1.2.1 specification as there are already various implementations of SYCL 1.2.1 in existence. The SYCL 2020 specification will only be mentioned to clarify any pertinent differences.

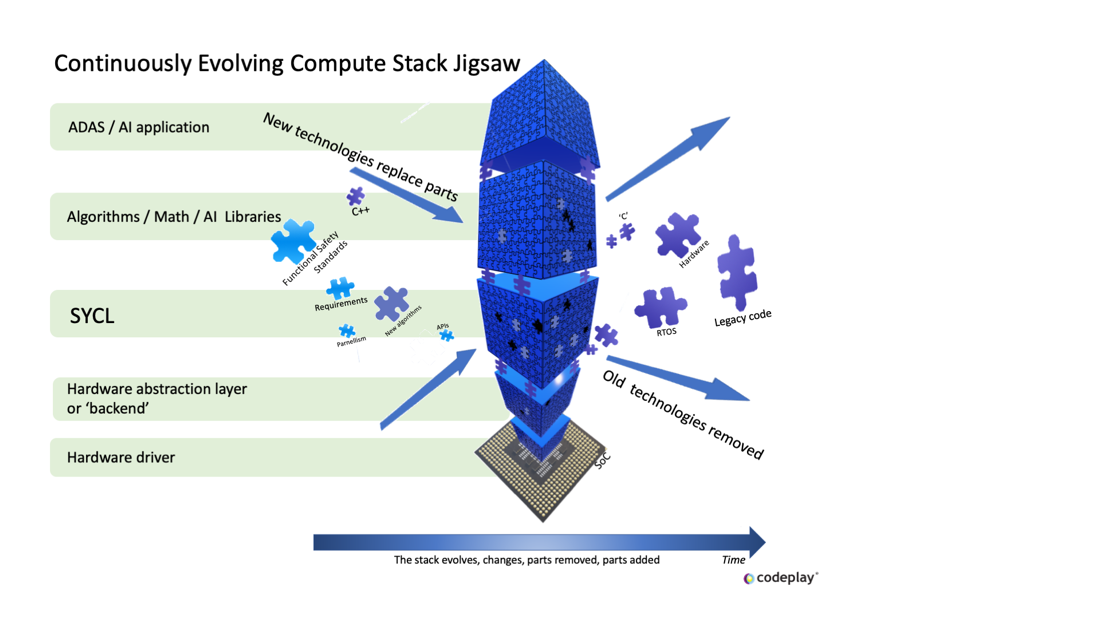

Figure 1: The SYCL computing stack layers

Referring to figure 1, most SYCL implementations do not talk to the hardware directly, they use a backend layer which is hidden from the application developer. The backend handles the rudimentary details of managing the acceleration device. As part of that cooperation the SYCL implementation communicates the capabilities of the device to the developer and conversely the developer pushes kernels and data down to the device.

SYCL enables the developer to gradually optimize features using high-level programming simplicity without giving up control over low-level performance when needed. The most commonly used backend is an OpenCL implementation. OpenCL is an open standard that has been in use since 2008. A thing to note about OpenCL: while it too is a Khronos API specification, each implementation is customized to target a specific hardware platform or discrete device. All the SYCL implementations follow the SYCL specification closely, but ComputeCpp is the only one that has been certified SYCL 1.2.1 conformant by Khronos. As SYCL is an open standard and freely available, an implementor has the freedom to develop an implementation with added features (or extensions as they are called) optimized for a specific device. Do note though that an implementation cannot carry the Khronos SYCL name or logo unless it is conformant, in case this is a requirement for your project. A critical 1.2.1 specification requirement for it to be conformant is that it must be able to use an OpenCL library as its backend layer. The SYCL 2020 specification removed this requirement. Another important point to note about the word "conformant" is that it does not concern itself with performance, nor functional safety requirements of any kind, it represents only functional conformance.

You may well be aware that SYCL is heavily intertwined with the high-level programming language C++. The philosophy of SYCL has always been to align with the direction of the ISO C++ language standard, not to employ any C++ language extensions, and importantly work with existing C++ compilers. The SYCL 1.2.1 specification supports C++ '11 as a minimum with the freedom to utilize more modern features available in C++ '14 and C++ '17 if desired, and the implementation supports it. SYCL 2020 requires support for C++ '17 directly.

The SYCL C++ API allows the developer to seamlessly integrate it with their application. This means it is possible to integrate SYCL with other interfaces (for example the Eigen linear algebra library or Google's® TensorFlow™ machine learning framework). Unlike the highly parallel computing code bases developed using OpenCL, SYCL allows the developers to create applications with the acceleration device kernels embedded in the application code which enables them to develop abstractions to better fit their problem paradigm.

From the outset SYCL 1.2.1 was developed with parallelism in mind, to manage the execution of, and the delivery of data, to arrays of computing units. With that, SYCL's well defined memory model automatically sequences and manages data movement across the compute units on behalf of the programmer's directives, greatly reducing the inherent efforts that come with highly parallel programming. The implicit data management provided by SYCL 1.2.1 can be supplemented with USM (Unified Shared Memory) support by way of an extension, or directly with SYCL 2020. USM provides a unified address space (the programmer sees a contiguous block of memory mapping all devices in the same context and not several separate blocks) of the host CPU and the target acceleration devices. In contrast to the implicit "Accessor" data handling model used since SYCL's conception, USM enables developers to program in the more traditional manner using explicitly defined data movement directed by events, and pointers with direct access to data buffers. USM can provide a better fit for some problems today but in general SYCL buffers and accessors are likely to provide the best performance. The recent support for USM has come from members of the Khronos SYCL working group who want to support legacy programs used in the HPC community and the growing desire to port existing CUDA algorithms to non-proprietary hardware, which often use 'C' style pointer manipulation. The implicit Accessor data movement memory model very much lends itself to support safety as it reduces the chance of introducing systematic errors.

Automotive Functional Safety Standard ISO 26262

The motivation to create this series of articles has come from the enquires being made by automotive OEMs, Tier 1s, and various SoC computing device vendors. These questions relate to how SYCL can support the functional safety standard ISO 26262 and more specifically Chapter 6, the requirements for software. ISO 26262 is the de facto safety standard that most automotive vehicle manufacturers follow to make commercially available vehicles. It is a set of requirements for all electrical systems in a vehicle generally contained within an Electronic Control Unit (ECU).

Chapter 6 of ISO26262 asks for certain requirements of software being developed based on the criticality of the whole system to maintain safe operation and not cause the determined level of injury should it fail – Automotive Safety Integrity Level (ASIL). The given set of requirements are there to ensure the system and the software within operates safely on failure. This should not be confused with the intended behavior of the system working normally in its environment (covered under a future functional safety standard PAS/CD 21448SOTIF).

These technical articles are here to assist in providing insight into the safety concerns that can arise for most ADAS and AI applications using SYCL. It should be said that some of the topics are not just restricted to SYCL, but any application that uses a multi-threaded computing stack model.

To summarize, ISO 26262 requires that an application proves an explicit chain of reasoning:

- Identified hazard events for the system which would cause damage, injury or death

- Strategies used to remove unreasonable risk for each identified hazard event

- Safety goals that mitigate the unreasonable risk

- Hazard events assigned an ASIL level

- Assurance claims or requirements are then asserted such that each safety goal is satisfied by a supporting functional safety concept

To aid them in meeting their safety goals, various measures can be used by the developers of the stack such as, but not limited to, the following:

- Use of fault injection and detection

- Performing design and code review

- Verification of the safety requirements by means of testing and reporting

- Performing integration testing at all levels in the stack

- Identification of cascade events in the stack

- Develop supporting failure mitigation mechanisms

- Define a safe operational state to limit further system degradation

- A safe operational state is reached within the time of the potential hazard event occurring

It is recognized by the ISO 26262 standard that there are two types of failure; a random failure – an act of god, or a systematic failure – a fault introduced into the system by the developer. The potential number of vectors for introducing errors are many; integrating different codebases, coding experience, programming parallelism, the array of tools, communication, and the appreciation of edge cases causing cascade events.

ISO 26262 applied to SYCL

There are many advantages to using SYCL depending on your role in the development of an accelerated ADAS application and on your perspective of how features within it can support safety. Good engineering practices and safety go hand in hand and ISO 26262 provides a good baseline to work from at every level of operational criticality. From a safety perspective and if taken literally, some of ISO 26262's software requirements can paint the computing stack and its constituent parts in a bad light, to the point that it would disallow many features that enable the ADAS technology to work (notably dynamic memory management). When ISO 26262:2010 was first released it targeted a very different type of codebase: a simpler, smaller codebase written close to the hardware by a single Tier supplier with very few, if any, layers or different technologies involved. Its software development guidelines were aimed at programs written on a simple CPU (one core, one thread, no caches) in machine code or 'C' code. Yet the same rules from 2010 are being applied to the ADAS computing stack as depicted in figure 1. The automotive community has realized this. The ISO 26262 standard should be used as a reference to ensure its identified programming concerns are considered throughout an application's continuous development with supported reasoning. Some of SYCL's perceived negatives as seen by the ISO 26262 guidelines can and should be taken as positives when modern programming features aid the developer to write efficient, performant code. At the same time, the modern architecture of the components in the SYCL ADAS stack can help in reducing the introduction of systematic errors which is one of ISO 26262 key aims.

A SYCL stack supports the reduction of systematic errors by:

- Reduction or removal of boiler plate code

- Code is not manually repeated by individual developers

- One correct and tested component for many developers to use

- Support for extensive error handling

- Modern C++ resource handling

- Open source invites extensive code review and oversight

- Components/libraries support reuse of tried and tested validations

The challenge for anyone when applying ISO 26262 or any safety standard is that once released, they are already lagging behind the state-of-art in many areas of ADAS development. The authors of the ISO 26262 standard are aware of this disadvantage and are very careful not to recommend any specific tools for development. This does allow the user room for interpretation and reasoning when developing an ADAS application. A lot of the perceived negative programming practices or patterns identified by ISO 26262 before 2010, when brought into the greater context of writing complex applications, can be turned back into positives attributes. That being said, some of the other guidelines are still very much applicable today. An ADAS developer can concentrate on the problem at hand, the development of the application, and not be spread so thin across less familiar technologies throughout the stack. Table 1 lists the pros and cons of SYCL programming with a bias towards safety concerns.

| Positives | Perceived negatives |

|---|---|

| - Small code footprint - One C++ source file enables type-safety across both the host and the device code reducing systematic errors, which are caught automatically by the compiler - A kernel program written using the single source code model is the same code that can be executed on either the application host or target device (using a subset of C++) - The programmer can build up data and compute dependency graphs at compile-time enabling the mapping of a graph to the processors offline (C++ embedded domain programming) - Single source code improves the final performance of the kernels as a compiler can use the context outside of the kernel definition in addition to the kernel itself - The code pattern Separation of Concerns can easily be applied, so AI or ADAS algorithms are separate functions and therefore encouraging good engineering practices - Single-source code is generally quicker to write and debug - A kernel program can easily be debugged by targeting the host device - The code can describe the problem or workflow without the noise of the device implementation details and semantics of operating the device getting in the way - Any boilerplate code is kept to a minimum, moving the operational details into the SYCL implementation. An implementation is written once and used many times reducing programmer systematic errors. - Minimal code set-up and tear-down code - No proxy code is required between C++ host code and SYCL API interface - Minimal data type conversion required (and type checking) - Kernel program error handling code is not intrusive - SYCL allows for object-oriented code and high-level C++ abstractions - The SYCL API is available as open-standard and so allows inspection by any safety practitioner - A kernel program is able to execute on multiple compute devices; host, FPGA or GPU without modification - The “safety proven in use” argument can be applied, as existing C++ compilers can be used without modification to compile the application’s host side code - Uses only standard C++ ‘11 (including C++’14 features written in C++’11). Specialized language extensions are not used or required for SYCL programming - Device side memory handling automatically follows the C++ RAII programming idiom |

- Extensive implicit functionality - Implicit memory allocation handling - Some tools, compilers or libraries are open source, may have to fork a version - Some understanding of the target hardware is required in order to write the appropriate kernel code and data transfer strategies to get optimum performance - USM allows code to make extensive use of pointers (SYCL 2020 specification, ComputeCpp v2.0.0 beta feature) - USM allows for explicit memory handling code and data movement introducing risk of programmer systematic errors (SYCL 2020 specification, ComputeCpp v2.0.0 beta feature) - Kernel program error handling is optional for the developer |

Table 1: Positives and perceived negatives of SYCL programming from a safety perspective

While, as shown in figure 1, the SYCL implementation would likely sit in the middle of the stack, it has a very strong influence on how the whole stack is developed and operates. ISO 26262 favors decomposition and the notion of components with clean interfaces (software APIs). Decomposition enables any identified safety concerns to be compartmentalized with clear sight of ownership and mitigation responsibilities. With that ISO 26262 allows the addition of components which can mitigate safety concerns of those components which would be too arduous to refactor. A SYCL stack with open standards in its DNA supports this view. Using ComputeCpp, Codeplay's SYCL implementation with its mix of proprietary (Codeplay's source code can be made available for inspection by a customer) and open-source components can provide that important visibility that Safety Practitioners in the industry demand.

Various parts of the SYCL stack, as implied, are already open-source. Again, depending on your role and responsibilities in the development of a safe computing stack, open-source components can present opportunities that are compatible with ISO 26262 and its concerns. Table 2 highlights both.

| Opportunity | Concern | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Wide developer expertise and experience | Not all developers want or care for safety features | The industry is working on safety approaches for SYCL, including MISRA C++ |

| Wider range of implementations harden the API and code base | Not all features are suitable for safety applications | Fork the code and develop separately, control over the implementation |

| Public access to the code base and so can be inspected | Systematic errors easily introduced | Development of a test harness |

Table 2: Open-source software for safety applications

The SYCL implementation ComputeCpp, and the partial computing stack it sits in, can be described by ISO 26262 as a SEooC ("Safety Element out of Context", a component or item which is developed for safety, whose automotive use case is not known at the time). While it can been seen as a SEooC, it is a fully featured component which influences and is key to the operation of the whole compute stack. Once a customer completes the stack by providing a use case it can be customized and tuned to meet the needs of the customer.

Conclusion

To address every Functional Safety Managers' question "Is it safe?", this technical article, like the others in this series, cannot give you a definitive answer. The context of the SYCL implementation, the makeup of the computing stack, and how SYCL sits in it, cooperating with the application and its physical operating environment, are required. The aim is to give you some insight into the various parts from which you can derive your own conclusion. ComputeCpp has been developed in a commercial environment for computing performance. Until the criticality of the automotive use case is known, supported by a safety concept, the question cannot be fully answered. Does a SYCL implementation like ComputeCpp hinder safety or enhance safety? At this present time, I believe it is able to address the safety concerns. Is it a good alternative to other automotive compute stack models? Yes, I believe it is. The SYCL compute stack and all its various parts do present challenges that are unique to it but on the other hand, it does provide many opportunities for OEMs that are otherwise not available.

The interest and adoption of SYCL by the HPC community confirms SYCL's potential to deliver ever more computing performance while providing an open forum for different parties to contribute. The automotive industry is understandably more conservative in its approach, but is aware of the challenges of adopting functional safety standards which lag state-of-the-art ADAS application development. This and future technical articles will, I hope, provide the confidence that ComputeCpp or other SYCL implementations can operate in a safety environment because it stands on a platform of sharing information so that we can better formulate safety strategies.

List of Safety Practitioner articles

- Blog 1: SYCL for Safety Practitioners – Introduction https://www.codeplay.com/portal/blogs/2020/07/24/sycl-safety-part-1.html

Acronyms list

| Acronyms | Description |

|---|---|

| ADAS | Advanced Driver Assistance Systems |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programmable Interface, a frontend public-facing set of functions to a software library or component |

| ASIL | ISO 26262 Automotive Safety Integrity Level |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit hardware compute device |

| DPC++ | Intel's SYCL implementation Data Parallel C++ |

| DSP | Digital Signal Processor |

| ECU | (Automotive) Electronic Control Unit |

| FPGA | Field Programmable Gate Array hardware compute device |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit hardware compute device |

| HPC | High Performance Compute |

| ISO 26262 | Automotive Functional Safety Standard 2018 |

| OEM | (Automotive) Original Equipment Manufacturer |

| OpenCL | Khronos software API specification OpenCL |

| SEooC | ISO 26262 term System Engineered Out of Context of an automotive functional use case |

| SoC | System on Chip integrated circuit |

| SYCL | A Khronos API and implementation specification |

Useful URLs

Introduction to SYCL

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXejyI4-WEI&feature=youtu.be

SCYL programming learning material

https://sycl.tech

Khronos learning resources on SYCL

https://www.khronos.org/sycl/resources

ISO C++ and SYCL Join for the Future of Heterogeneous Programming

https://www.codeplay.com/portal/news/2020/06/09/iso-cpp-and-sycl-join-for-the-future-of-heterogeneous-programming.html

Codeplay

https://www.codeplay.com/

Intel DPC++

https://software.intel.com/content/www/us/en/develop/tools/oneapi.html

About the author

A generalist programmer with 24+ years of experience.

Illya works for Codeplay Software as a Principal Engineer since 2013 overseeing the development of tools chains for automotive semiconductor customers. He is the chair of the Khronos Safety Critical Advisory Forum (KSCAF) and a member of the Khronos OpenCL and Vulkan Safety Critical working groups. Illya is also a member of the MISRA C++ committee. Illya has a BSc (Hons) degree (in Electrical and Electronic Engineering) by the University of Surrey (UK) following a 4 years electronics apprenticeship at the MoD Royal Aircraft Establishment Farnborough (UK). After university he spent 12 years programming games, tool chains and profilers for major games consoles like Playstation 3 and Playstation Vita for Sony Computer Entertainment Europe followed by further 2 years in a Scottish indy games company improving performance and implementing anti-hack solutions for their open world multiplayer online video game.