SYCL for Safety Practitioners – An Introduction

13 July 2020

SYCL for Safety Practitioners Series

Part 1 - An Introduction

Part 2 - SYCL for Automotive AI and ADAS applications

Part 3 - SYCL ADAS Applications Topology Explained

There are many resources across the internet on functional safety in software, covering a substantial range of topics. What I recognized is that there are no resources for safety practitioners and programmers looking at developing applications with SYCL™ that are required to meet functional safety requirements. This is the first in a series of blog posts that will give readers an overview of what they need to know about using SYCL in a safety-critical environment. The information is most relevant to safety practitioners working with SYCL, but equally will help to educate developers working on low-level drivers for DSPs and other processors.

An Introduction to SYCL for Safety Practitioners

What is SYCL? What does a safety practitioner need to know about it? What does a Functional Safety Manager need to know to have a conversation with a SYCL programmer or architect to be able to question the design so that safety assurances can be made, and challenges defended?

Let’s start by talking about what SYCL is. It’s not an acronym, but it is an open standard specification from the Khronos® Group defining a single-source C++ programming layer that allows developers to leverage C++ features on a range of heterogeneous devices. A heterogeneous device is a platform with one or more CPUs with additional acceleration devices like GPUs, DSPs, and FPGAs. SYCL takes advantage of heterogeneous hardware architectures that enable parallel execution to provide a foundation for creating efficient, portable, and reusable middleware libraries and accelerated applications. If you want to find out more about SYCL the SYCL.tech community website is a good place to start.

My goal is to create a comprehensive guide to getting an overview of a typical SYCL implementation design by visiting topics related to using SYCL to develop safety applications.

I have started this introduction implying this series of blogs is targeted to safety practitioners. This is true, but any person interested in developing with SYCL can also benefit from them. You will also benefit if you are a seasoned DSP programmer, a Nvidia® CUDA programmer, or a low level programmer hitting the hardware ‘C’. There is a cross over between well-crafted code that makes maximum use of the hardware and that same code meeting safety criteria. The blogs will be presented in a loose logical order, with blogs expanding on a previous blog, but due to the range of topics that will be covered, some can be read out of order. The blogs provide a high-level overview with enough depth to give you a good understanding of how things work while deducing where safety concerns may lie. That being said, the blogs also aim to highlight the benefits of using SYCL for safety applications.

This is not another ‘learn how to program’ using SYCL series, there are plenty of existing materials for that including the open-source SYCL Academy project. The blogs purposefully take the approach of breaking open the application’s ‘data compute stack’. SYCL is just one of the many components that need to work in harmony, in what is a multi-faceted application, to usually perform one task like valet parking or adaptive cruise control.

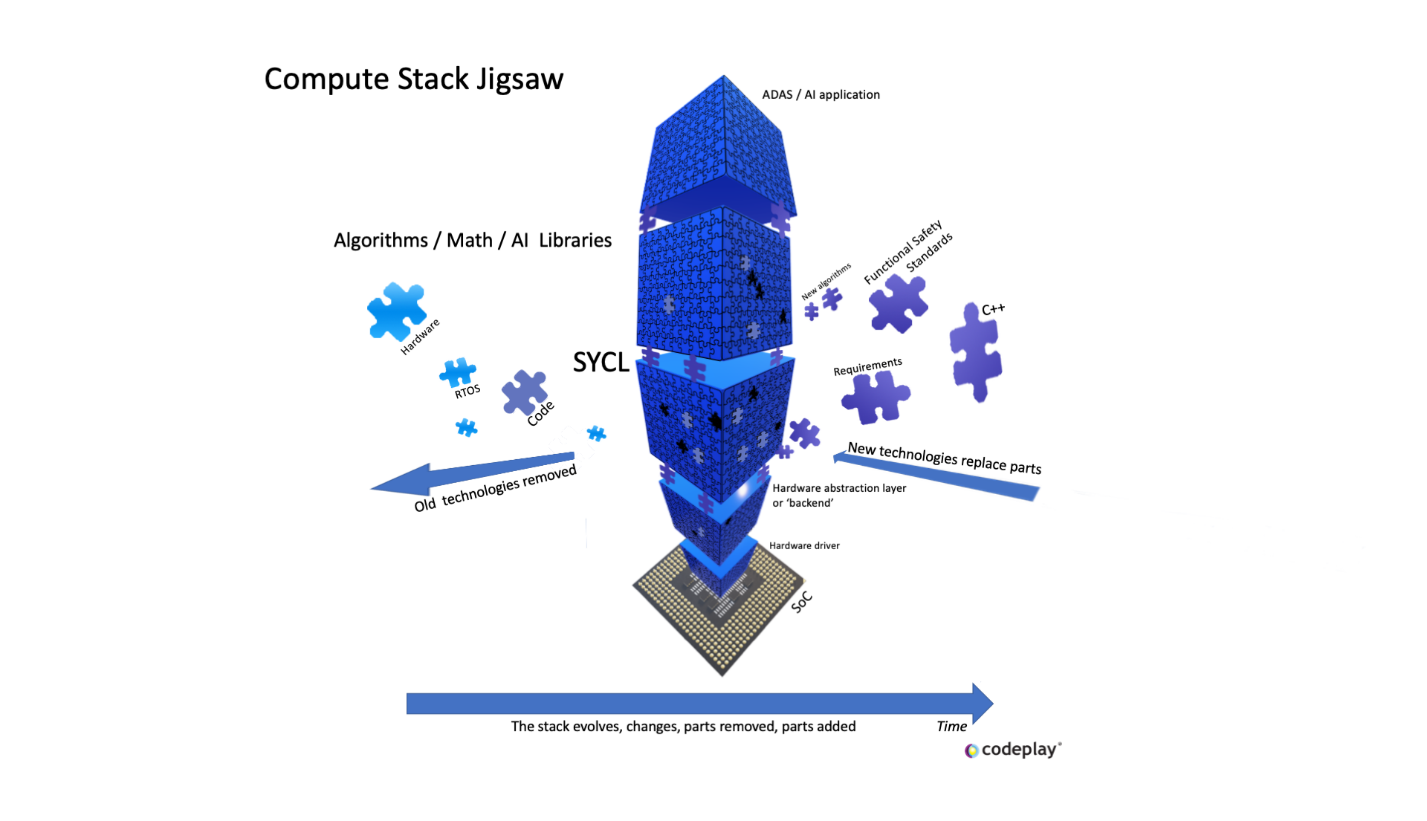

Figure 1: The evolving ADAS AI application compute stack

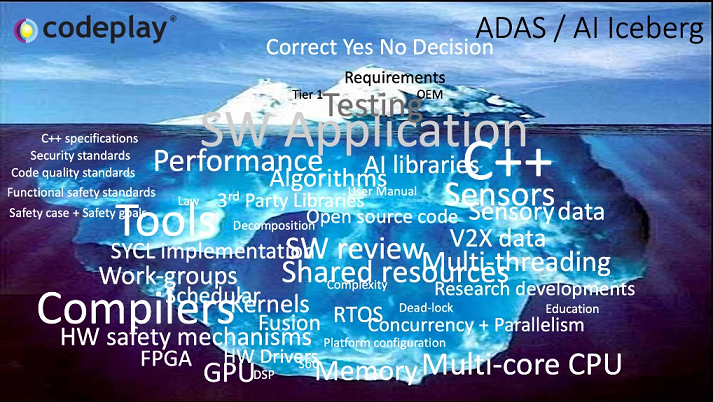

This series of blogs won’t go into the details of ComputeCpp™, a commercial SYCL implementation by Codeplay Software and the first Khronos conformant implementation in the world. These blogs are here to layout the SYCL ecosystem, and to reveal some of SYCL’s inner workings as a functional safety practitioner would want it so that safety concerns can be noted and addressed accordingly. SYCL is portrayed in the many presentations and articles as an easy to use parallel programming solution and in my opinion, having worked with many APIs and SDKs in the past, it is easy to use once you think about processing in parallel. Below the tip of the iceberg called ‘SYCL’ or ‘AI application’ is a myriad of components, layers, tools, C++ language issues, open-source code and so on. All these things are commonly wrapped up in a single word ‘SYCL’ and need to be broken out and examined by a safety practitioner.

SYCL as an open-standard

There are quite a few different SYCL implementations in existence. Each implementation vendor brings with them new perspectives and ‘solutions’ to help them differentiate their products. This is expected and it is done all the time but much of the technology that goes into SYCL and the supporting backends has been around for a good number of years. As a practitioner, it does help to have the correct perspective of the history, to understand why things were done the way they were, for better or for worse. So these blogs, where appropriate, will point out the similarities or differences between implementations. They will also bring together the different names or terms used to reduce any confusion. This is very much a learning step for everyone, so the blogs are not complete since AI acceleration for functional safety is a developing technology. I would also invite you to contribute to these blogs, clarify any points I have made or add new topics that relate to the stack in the context of functional safety.

Another consideration that can be overlooked is the fact that SYCL is an open standard specification which can bring many benefits with it. One of these is that the specification is defined by a working group, and this group defines new features and changes to the standard. The focus in the working group has primarily been on delivering a specification to provide performance and coding agility. But there is also an opportunity to join Khronos and take part in the working group meetings, to bring functional safety expertise and input for the evolution of the standard.

Continuous Development - The computing stack evolves, some software becomes “legacy,” algorithms get improved, and new algorithms are found to replace the ones that are no longer suitable. In the dynamic world where there are few considerations for safety requirements, the technology and its software will evolve very fast, a good thing as it drives innovation forward. Faster innovation and iterative development is part of the attraction that the automotive industry is seeing as a way to obtain the next generation of vehicle features that consumers want, and regulations stipulate. A reason for this is it can be cheaper and quicker to ramp up production than start from scratch each time. Another consideration for automotive OEMs is that they are looking for alternatives to being tied to one specific hardware architecture or vendor to power the software for future generations of their vehicles. A lot of the open-source projects being used by researchers are not developed following functional safety standards, but these are likely to be evolved to be used in a safety critical environment too. Once this technology is brought into the automotive domain, the speed of evolution that was delivering the rapid technology research stalls as it has to follow safety processes and meet specific operation safety requirements. The developers who work in open-source communities do not necessarily have a vested interest in safety applications, and while they help evolve the software, there may not be considerations in supporting software for safety purposes. The burden of work now falls on the safety application developers to evolve the tools and software, often with a much smaller number of people.

Starting with vector addition

As you can see, there are many facets to SYCL development for safety that are not immediately obvious from the many tutorials on how to write a simple vector addition application. There are also SYCL programming paradigms that have not been commonly seen in a safety environment which this series of blogs aims to highlight. I will visit a topic, giving a fairly in-depth overview so that you can go away and have a conversation with a colleague or developer. You could look at this as the SYCL encyclopedia as it were, a growing encyclopedia. As a safety practitioner, you want to know how SYCL works and what it means to deliver an application using SYCL.

As I have mentioned, there is a growing quantity of good-quality learning material available, but most of it focuses purely on programming with SYCL. For a safety practitioner or a company looking to invest in SYCL for safety applications, they want to know the good and the bad so that they can better appreciate what it means to write safety applications, while meeting the guidelines and requirements of current and future automotive functional safety standards like ISO 26262, SOTIF, IEEE guidelines and UL4600. For safety practitioners not versed in C++ or parallel programming, it is likely they will not know what to be concerned about and I will try to help you to understand the issues. There are plenty of conference presentations, YouTube videos, papers, and blogs on advanced SYCL programming across the internet, but the intention here is to bring the functional safety relevant information into a single place.

Ultimately these blogs are here to reveal the makeup of a SYCL implementation, poke and prod it, with the aim that practitioners can go away and appreciate what is required so that we can safely tune our SYCL applications with confidence. One of the present challenges today for a SYCL implementation is that it is developed out of the context of any particular automotive use case (an ISO 26262 SEooC). The SYCL implementation cannot provide any safety assurances if it is not considered alongside the computing stack it is operating in. It would be unwise to provide assumed safety assurances which are later broken by unknown operational resonance frequencies while operating under real-world conditions. An example of operational resonance frequencies and how it can cause failure is the Thames footbridge in London. When installed it would start swaying side to side when people walked across it. The engineers had not taken into account people walking across the bridge in step unison. This unconscious behavior by pedestrians causes the bridge to oscillate in increasing amplitude inducing it to sway, potentially leading to the bridge breaking. This analogy could be applied to an application using a compute stack where one or more layers could ‘resonate’ causing results or behavior to diverge from the expected norm.

Let me now give you an example of a SEooC component and operational failure. This is a story of a software component used for one use case scenario and which worked as expected. It was then moved to another project which then caused a catastrophic failure in a subsequent ‘exact’ same use case. The program for a unit on the Ariane 4 spacecraft reads data from several sensors and can handle 16-bits wide word length. The program would take the input data and process it before sending it on to the main processing unit for flight navigation. Some of the sensors returned 64-bit data which had to be acknowledged and handled appropriately to work with 16-bits wide words. To keep within a strict battery power budget the software would not check all the data returned to it, only when it got 64-bit data from the sensors. The rocket flew fine. The same sensory processing unit was then put in the Ariane 5 rocket. It blew up 40 seconds after take-off. The reason was tracked down to a new 64-bit sensor replacing a previously 16-bit sensor. The 64-bit data overflowed into neighboring memory space and caused the program to crash and report a debug error. That error message was sent down the same channel that was used by the data for the navigation unit. The navigation unit had never seen a debug message before and so interpreted it as flight data and adjusted the rocket to correct for the new direction it believed it was flying in, but the rocket was not flying incorrectly in the first place. Other systems on the rocket saw it was now flying badly and so blew it up. This is an example of a layered system with discrete processing layers each communicating data, very much like the ADAS compute stack.

What does become come clear while brainstorming and researching each topic, is just how much bigger the landscape is than initially envisaged when starting to write these blogs, “What does a safety practitioner need to know about SYCL?” The topics are spread wide but may not be very deep. Yes, there is always more to be included on any topic but there is enough information here for a safety practitioner to start with. Yes, these blogs do not provide all the answers, the industry will evolve with this in time. They provide a platform on which the safety concerns can be identified, scope ascertained and build a conversation towards providing necessary safety assurances, if and when they are challenged in the future.

Finally, another aim of these blogs is to allow a person to quickly get up to speed and understand what it means to use SYCL. Its aim is to de-mystify the myriad of terms and definitions surrounding SYCL and parallel programming that people use with no further explanation, e.g. “This PC has LRF support” where LRF is an acronym for ‘Little Rubber Feet’. Many different terms can mean the same thing or something different depending on the context. To me, I find this rather frustrating and can lead to wasting time searching for something ‘new’ only to find it means the same thing. So, where possible I have unified terms to allow the reader to make the connection, should they only know it by one of the definitions. I have also purposefully, for my sanity, tried to clarify definitions where they could get mixed up with meaning the same thing when they are not, e.g. race condition, dead-lock, and data race. As a safety practitioner, we need to be clear in our communication and intent.

Summary

The compute stack represents an iceberg of technologies, standards and players. The SYCL implementation which sits in the stack is part of a Russian doll and is a Russian doll itself. Open it up and it reveals more technologies and safety concerns. These blogs will try to layout those technologies and highlight some of the concerns.

The series continues with part 2 - SYCL for Automotive AI and ADAS applications

About the Author

A generalist programmer with 24+ years of experience.

Illya has worked for Codeplay Software as a Principal Engineer since 2013 overseeing the development of tools chains for automotive semiconductor customers. He is the chair of the Khronos Safety Critical Advisory Forum (KSCAF) and a member of the Khronos OpenCL and Vulkan Safety Critical working groups. Illya is also a member of the MISRA C++ committee. Illya has a BSc (Hons) degree (in Electrical and Electronic Engineering) from the University of Surrey (UK) following a 4 years electronics apprenticeship at the MoD Royal Aircraft Establishment Farnborough (UK). After university he spent 12 years programming games, tool chains and profilers for major games consoles like Playstation®3 and Playstation Vita for Sony Computer Entertainment Europe followed by further 2 years in a Scottish indy games company improving performance and implementing anti-hack solutions for their open world multiplayer online video game.

Acronyms List

- ADAS - Advanced Driver Assistance Systems

- AI - Artificial Intelligence

- API - Application Programmable Interface, a front-end public-facing set of functions to a software library or component

- CPU - Central Processing Unit hardware compute device

- CUDA - Nvidia’s proprietary C++ parallel programming language for Nvidia hardware

- DSP - Digital Signal Processor

- FPGA - Field Programmable Gate Array hardware compute device

- GPU - Graphics Processing Unit hardware compute device

- IEEE - Institute of Electrical and Electrical Engineering

- ISO 26262 - Automotive Functional Safety Standard 2018

- LRF - Little Rubber Feet

- PC - Personal Computer

- SDK - Software development kit for specific hardware

- SEooC - ISO 26262 term System Engineered Out Of Context of an automotive functional use case

- SOTIF - ISO committee safety standard in development Safety Of The Intended Functionality and is closely linked to ISO 26262 meant for dealing with autonomous driving with ML and covers all SAE levels

- SYCL - A Khronos API and implementation specification for heterogeneous modern C++ suitable for CPU, GPU, FPGA, and AI processors

- UL4600 - Safety standard from Underwriter’s Lab and it describes a safety case approach using what-if scenarios to ensure autonomous product safety for SAE Level 5.

List of useful URLs

- SYCL Community News and Resources website

- Introduction to SYCL

- SYCL 1.2.1 specification

- SCYL Academy

- Codeplay Software website

- Codeplay Developer website

- Intel DPC++